VR-HEU's Moment of Truth

The following is an extract from Chic's book Syd's Last Pirate.

Chapter Thirteen

VR-HEU’S Moment of Truth

`No one can shorten my life by a minute. It belongs to God,’ Ghandi.

That 23 July 1954 began as C.S.V.U. – clear sky visibility unlimited. It was a day when even the most restless soul found tranquillity. However, as the minutes ticked by, aerial murder would reduce it to another day in infamy. The dramatic change began when a breathless radio operator handed a message to Pip Pickering, the Kai Tak Duty Controller. It read:

`Mayday! Mayday! VR-HEU going down, engine on fire,

Chapter Thirteen

VR-HEU’S Moment of Truth

`No one can shorten my life by a minute. It belongs to God,’ Ghandi.

That 23 July 1954 began as C.S.V.U. – clear sky visibility unlimited. It was a day when even the most restless soul found tranquillity. However, as the minutes ticked by, aerial murder would reduce it to another day in infamy. The dramatic change began when a breathless radio operator handed a message to Pip Pickering, the Kai Tak Duty Controller. It read:

`Mayday! Mayday! VR-HEU going down, engine on fire,

However, even as Pip read the message, Cathay Pacific’s Skymaster had slipped beneath the restless waves of the China Sea, a flaming pyre, the victim of an attack by Chinese Communist fighter planes operating from San Ya (Yaxian). This is a military aerodrome at the southern extremity of Hainan Island.

Days before the attack the writing was on the wall, but unfortunately the authorities overlooked its significance.

Captain Len Cos Cosgrove had left Saigon’s beleaguered airport of Tan Son Nhut after a brief wait for the morning fog to clear. He had breakfasted with thirty French Air Force pilots ready to scramble the Corsairs and Martlets that stood in the dispersal bays. Each aircraft had a full load of napalm cylinders slung under the wings. Their assignment was another foray against the Viet Minh. The fog cleared, the Air France Constellation from Paris landed, and Cos took off.

He knew the Indo China coast intimately and the chart he carried was a formality. The weather between Vietnam and China is benevolent, with sunny skies prevailing, except for the seasonal typhoons that quickly destroy that peace.

This July day had an air of tranquillity with typhoons a bad memory. As his venerable Catalina droned above the gentle sea Cos felt an insidious lethargy. With a start he scanned his instruments. His height 9,000 feet, with 103 knots of airspeed, outside air temperature 8 degrees Centigrade and fuel consumption 65 gallons-per-hour, everything spot-on. His mind wandered to just three and half-hours to Hong Kong and a weekend’s fishing. Through drooping lids he saw the brown mass of Hainan Island to port. Then as the distance closed the old war time strip of San-ya drifted into view. His mind flitted to the day in 1950 he landed there to take Kuomintang refugees to Macau.

Suddenly he stiffened, for the strip, barely an inch-long at this height, looked very different. Concrete patches were etched at each end of the bitumen runway. Oh boy! That means jets! thought Cos. Through field glasses he found newly built dispersal bays ready to receive their charges.

There was the writing on the wall for sure, mused Cos. He would give Hainan Island even greater clearance in future. He discussed his findings with his co-pilot, Jim Kiernan and Winyard, his flight engineer, but as the miles reeled off he pushed it to the back of his mind.

On

landing he phoned a senior official of the Department of Civil Aviation

with his concerns and pointed out the implications. The official

expressed little interest and the traffic lanes near Hainan Island

remained unaltered with no formal warning issued.

The highly respected QANTAS Captain Forgan-Smith had command of a Constellation proceeding from Sydney to Tokyo. The flight’s timetable scheduled landings at Labaun, Hong Kong’s Kai Tak and Iwakuni.

In a position abeam of Hainan Island his first officer Arthur Whitmarsh suddenly threw his lunch tray into the companionway and grabbed the controls. A dark grey high-tailed jet zoomed up from underneath and disappeared almost vertically on the port side.

It passed so close we could smell the kero exhaust from it, Forgie told me. He logged the position and reported the incident at Kai Tak. The senior official told him he must have mistaken the type. Everyone knew jets could not operate that distance from land!

The next morning, Forgie said, I was walking with the QANTAS agent when we overtook one of our onward passengers. As we passed he demanded to know why a grey painted plane had intercepted us. In a loud voice he stated it frightened the crap out of him!

I was a bit wary and asked him to describe it, said Forgie. He said it was a darkish high tailed jet. It came in from the right side, but by the time he put down his tray and raced to the port side it had disappeared. He thought it might have been an F86 or a Mig-Yak. He had engaged similar aircraft in Korea where he had been a Lieutenant Commander in the U.S. Navy.

I immediately turned him round and we went to the flight-checking section where he repeated the whole story. The senior man now listened with greater care than he had given to me. He made copious notes but I don’t think there was a follow up.

The highly respected QANTAS Captain Forgan-Smith had command of a Constellation proceeding from Sydney to Tokyo. The flight’s timetable scheduled landings at Labaun, Hong Kong’s Kai Tak and Iwakuni.

In a position abeam of Hainan Island his first officer Arthur Whitmarsh suddenly threw his lunch tray into the companionway and grabbed the controls. A dark grey high-tailed jet zoomed up from underneath and disappeared almost vertically on the port side.

It passed so close we could smell the kero exhaust from it, Forgie told me. He logged the position and reported the incident at Kai Tak. The senior official told him he must have mistaken the type. Everyone knew jets could not operate that distance from land!

The next morning, Forgie said, I was walking with the QANTAS agent when we overtook one of our onward passengers. As we passed he demanded to know why a grey painted plane had intercepted us. In a loud voice he stated it frightened the crap out of him!

I was a bit wary and asked him to describe it, said Forgie. He said it was a darkish high tailed jet. It came in from the right side, but by the time he put down his tray and raced to the port side it had disappeared. He thought it might have been an F86 or a Mig-Yak. He had engaged similar aircraft in Korea where he had been a Lieutenant Commander in the U.S. Navy.

I immediately turned him round and we went to the flight-checking section where he repeated the whole story. The senior man now listened with greater care than he had given to me. He made copious notes but I don’t think there was a follow up.

On his pre-departure check in Saigon two days before VR-HEU’s murder, Captain John Carrington found the port oleo strut needed air pressure. The equipment to rectify this had to be brought from the city. Finally, with the problem solved the skipper realised the plane could not return to Kai Tak before nightfall. The Hong Kong authorities then forbade night flying except in a grave emergency.

This meant that the Bangkok-Singapore service must be rescheduled, but by getting his flight to Kai Tak at first light the next morning that would ease the delay. Captain Carrington and his crew spent a reasonable

night bedded down in their plane. Unbeknown to them, the Viet Minh had raided the airport’s perimeter shortly after midnight. When the skipper submitted a flight clearance he learned there would be a further delay while a bomb squad checked the runway for mines. He finally left Saigon and landed at Kai Tak shortly after 10:00 hours.

Captain Philip Blown took command of VR-HEU. His crew was co-pilot Captain Cedric Carlton, R/O Stephen Wong, and two hostesses Esther Law and Rose Chen. The cockpit crew would over-night at Bangkok and pick up the service to Hong Kong the next day, however Esther and Rose would do the whole flight to Singapore and return.

The next morning VR-HEU returned to Bangkok having made up 15 minutes. When Captain Blown arrived at the plane he found Cathay Pacific’s Bangkok ground engineer George Cattanach waiting for him. George Capt. Philip Blownwas a passenger and would be representing Cathay Pacific at a Department of Civil Aviation conference in the Colony. He was a well-known Hong Kong aviation identity and one who had survived his share of aviation mishaps. His most exciting brush with death was when a Catalina PBY-5A, with the nose wheel door slightly open, disintegrated in a geyser of tortured spray while landing in Kowloon Bay.

George was looking forward to the trip, for at the other end was his fiancee, Daisy Smith, who had an ill-defined job with Cathay Pacific. Her duties included engineering drafting and associated illustrations. She was also Bob Smith’s sister, which rated her first class on its own!

The smile left Captain Blown’s face when he read the snag book. A magneto drop on the No. 3 engine must be rectified before departure. George Cattanach made the rectification, but as he wrote off the snag he added a note that his work should be re-checked when VR-HEU got back to Kai Tak, for he suspected the timing of the engine had slipped. All this proved unnecessary, but how could he know that neither he nor the aeroplane would reach Hong Kong.

Finally, the passengers were loaded and Phil remarked that even though they had lost more time things could be worse! They continued to worsen, for when he tried to start No. 1 engine the starter would not mesh. He ordered the passengers to disembark, made a three-engine take-off and impulse started the engine in the air, returned and loaded the passengers. At last they were winging towards their appointment with destiny!

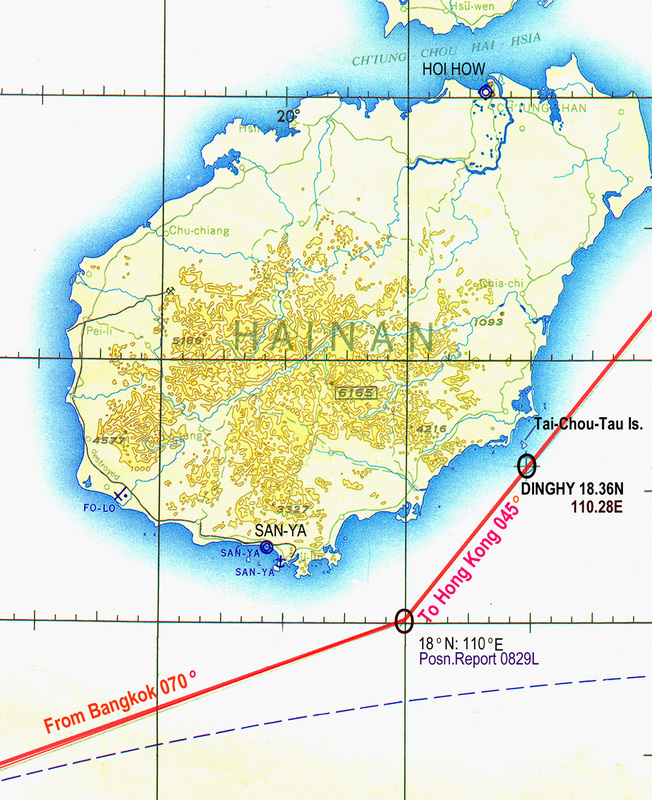

Steve Wong transmitted his last position report as a mortal at 08:29 hour’s local standard time (LST). That position was the mandatory checkpoint at 18 degrees North Latitude and 110 degrees East Longitude at 9,000 feet altitude. At 08:30 hours LST Phil Blown gently wound the autopilot knob to the left and changed the heading from 070 degrees to 045 degrees. That brought the airliner on a course paralleling the East Coast of Hainan Island some fifteen or twenty miles to port.

After about three minutes on this course Cedric Carlton excitedly reported a Chinese marked low wing aircraft closing in fast from above. Phil Blown looked through his side-window and saw another fighter diving towards his command.

As he disengaged the autopilot both fighters opened up with machine-gun and cannon fire. The noise of the firing was nerve racking.

The initial bursts set No. 1 and No. 4 engines on fire. Other bullets ruptured the fuel tanks in the starboard wing, which became a searing mass of flame. The skipper hurled the Skymaster into a dive. His evasive action, first to port, then to starboard, drew increased fire from the killer plane on the side he turned. There was no possible evasion for his doomed civilian airliner

Speed in the dive now exceeded 350 miles per hour, a full 100 miles an hour above the design speed for the wing. Phil saw this as his only hope of outflying the fighters. He prayed that the wings would remain attached to the fuselage. He hoped the speed would suck out much of the burning fuel from the gaping tanks. Perhaps, the speed would dampen the fire that enveloped the whole starboard wing.

What a lot of hopes and maybes, he thought!

The No. 4 engine screamed as it ran wild. The flight deck was a pit of hellish chaos. With superhuman strength, Phil fought the vibrating controls as Cedric reduced the power on the run-away engine until he could feather its propeller and the terrifying nerve shattering screech of tortured metal abated.

He pushed the CO2 discharge button. This smothered the fire in the No. 4-engine fire. But he had no way of fighting the blaze in the starboard wing.

Throughout, the Communist murderers poured continuous fire into the doomed airliner, and many passengers had died by bullet and shell blast. Phil and Cedric found themselves cringing as projectiles screamed up the main aisle. They ducked as glass projectiles from boost and fuel gauges sought their eyes.

Meanwhile, the cabin crew was handling their assigned duties with a calmness that reflected both dedication and first-class training. Radio Officer Steve Wong was upholding the highest traditions of his craft. Although Hong Kong had acknowledged his distress signal he continued transmitting. Unbeknown to him his latter messages were stillborn, as his aerials had been blasted away.

Realising that a calamitous ditching lay just moments away, Cathay’s Bangkok station engineer George Cattanach put a flotation vest on an injured passenger. As he turned to see what else he could do he saw hostess Rose Chen take a shell blast that tore her slight frame to shreds. As he scrambled towards her he joined her in eternity. Meanwhile, Ester Law had scrambled along the bullet ridden aisle to investigate a loud sucking noise. She threw open the toilet-door and saw a gaping hole in the roof. At that moment the John disappeared through the hole, and recalled saying to herself – That doesn’t look too good! and hastily slammed the door.

Mr Peter S. Thatcher saw his friend Leonard L Parrish kiss his two sons, Laurence 4, and two year old Phillip. He gently laid his massive frame over them in protection.

Time seemed to stand still with no panic or hysteria. At 5000 feet the rudder controls were shot away. At 3000 feet a bullet tore away the starboard aileron control but the gallant skipper felt some response from the port aileron. That moment of relief ended when the plane corkscrewed to the right. He controlled this by throttling back his two left engines and increasing his No. 3 engine to maximum power.

What a lot of hopes and maybes, he thought!

The No. 4 engine screamed as it ran wild. The flight deck was a pit of hellish chaos. With superhuman strength, Phil fought the vibrating controls as Cedric reduced the power on the run-away engine until he could feather its propeller and the terrifying nerve shattering screech of tortured metal abated.

He pushed the CO2 discharge button. This smothered the fire in the No. 4-engine fire. But he had no way of fighting the blaze in the starboard wing.

Throughout, the Communist murderers poured continuous fire into the doomed airliner, and many passengers had died by bullet and shell blast. Phil and Cedric found themselves cringing as projectiles screamed up the main aisle. They ducked as glass projectiles from boost and fuel gauges sought their eyes.

Meanwhile, the cabin crew was handling their assigned duties with a calmness that reflected both dedication and first-class training. Radio Officer Steve Wong was upholding the highest traditions of his craft. Although Hong Kong had acknowledged his distress signal he continued transmitting. Unbeknown to him his latter messages were stillborn, as his aerials had been blasted away.

Realising that a calamitous ditching lay just moments away, Cathay’s Bangkok station engineer George Cattanach put a flotation vest on an injured passenger. As he turned to see what else he could do he saw hostess Rose Chen take a shell blast that tore her slight frame to shreds. As he scrambled towards her he joined her in eternity. Meanwhile, Ester Law had scrambled along the bullet ridden aisle to investigate a loud sucking noise. She threw open the toilet-door and saw a gaping hole in the roof. At that moment the John disappeared through the hole, and recalled saying to herself – That doesn’t look too good! and hastily slammed the door.

Mr Peter S. Thatcher saw his friend Leonard L Parrish kiss his two sons, Laurence 4, and two year old Phillip. He gently laid his massive frame over them in protection.

Time seemed to stand still with no panic or hysteria. At 5000 feet the rudder controls were shot away. At 3000 feet a bullet tore away the starboard aileron control but the gallant skipper felt some response from the port aileron. That moment of relief ended when the plane corkscrewed to the right. He controlled this by throttling back his two left engines and increasing his No. 3 engine to maximum power.

Gradually he reduced his speed to 160 miles an hour, but anything below this caused his starboard wing to stall out. He accepted this speed and prepared to hit the water.

With super-human strength he broke the descent as the doomed Skymaster skimmed the crest of a wave and the starboard wing tore off between its two engines. The pilots knew that the next impact would decide death or survival. The cockpit ploughed into a fifteen-foot swell about a quarter of the way from the crest. The severe deceleration snapped their safety harnesses hurling them against the rubber crash guards above the instrument panel. The water stove in the co-pilot’s cabin window and the skipper’s hinged clear-vision screen as a torrent of green water surged into the flight deck. After several false starts the pilots managed to assist each other to a miraculous escape.

From the moment the airliner came under attack until it slammed into the sea just two minutes had elapsed. When Cedric surfaced he saw a few survivors. He swam around telling them to grab mailbags and anything to help them float. Suddenly a Mae West bobbed up right in front of him. He struggled into it. Then he swam to help Peter Thatcher support a woman. She had a deep gash across her throat. It was not bleeding and she looked very grey. He could find no life in her, but slipped a Mae West onto her before going to help others. He had a moment of hope and joyously yelled you little beauty. As he saw Mrs Thorburn grimly grasping a twenty-man dinghy.

He continues, I was a bit concerned that if I inflated it too soon it might blow away. So I gathered everyone round it and then pulled the inflation cord. Within a few minutes all survivors were aboard’ - Cedric’s watch showed it was 09:00 hours.

As Captain Blown trod water he watched the burning wing slip slowly beneath the waves. The fuselage and finally the tail followed it. Then he gathered five white canvas cases and inflated the Mae Wests they contained. Pushing them ahead of him he found Peter Thatcher holding a woman. He told Peter the woman was beyond help and asked him to help check the area for survivors. They found three lifeless bodies and identified them as Mrs Finlay, Miss Rose Chen and one of the Parrish boys. Meanwhile Cedric had inflated the dinghy and pulled aboard survivors. Once aboard Phil assumed command. There were nine survivors, some with injuries. Three had bullet and shrapnel wounds and one had a broken thigh.

Concerned that the fighters would attempt to conceal their murderous deed he ordered they continue to wear their inflated Mae Wests. They should jump into the water if strafing began. As the fighters turned for San ya they erected the dinghy’s weather awning and closed the entry flap. This would give the appearance of an empty raft.

With super-human strength he broke the descent as the doomed Skymaster skimmed the crest of a wave and the starboard wing tore off between its two engines. The pilots knew that the next impact would decide death or survival. The cockpit ploughed into a fifteen-foot swell about a quarter of the way from the crest. The severe deceleration snapped their safety harnesses hurling them against the rubber crash guards above the instrument panel. The water stove in the co-pilot’s cabin window and the skipper’s hinged clear-vision screen as a torrent of green water surged into the flight deck. After several false starts the pilots managed to assist each other to a miraculous escape.

From the moment the airliner came under attack until it slammed into the sea just two minutes had elapsed. When Cedric surfaced he saw a few survivors. He swam around telling them to grab mailbags and anything to help them float. Suddenly a Mae West bobbed up right in front of him. He struggled into it. Then he swam to help Peter Thatcher support a woman. She had a deep gash across her throat. It was not bleeding and she looked very grey. He could find no life in her, but slipped a Mae West onto her before going to help others. He had a moment of hope and joyously yelled you little beauty. As he saw Mrs Thorburn grimly grasping a twenty-man dinghy.

He continues, I was a bit concerned that if I inflated it too soon it might blow away. So I gathered everyone round it and then pulled the inflation cord. Within a few minutes all survivors were aboard’ - Cedric’s watch showed it was 09:00 hours.

As Captain Blown trod water he watched the burning wing slip slowly beneath the waves. The fuselage and finally the tail followed it. Then he gathered five white canvas cases and inflated the Mae Wests they contained. Pushing them ahead of him he found Peter Thatcher holding a woman. He told Peter the woman was beyond help and asked him to help check the area for survivors. They found three lifeless bodies and identified them as Mrs Finlay, Miss Rose Chen and one of the Parrish boys. Meanwhile Cedric had inflated the dinghy and pulled aboard survivors. Once aboard Phil assumed command. There were nine survivors, some with injuries. Three had bullet and shrapnel wounds and one had a broken thigh.

Concerned that the fighters would attempt to conceal their murderous deed he ordered they continue to wear their inflated Mae Wests. They should jump into the water if strafing began. As the fighters turned for San ya they erected the dinghy’s weather awning and closed the entry flap. This would give the appearance of an empty raft.

At 11:25 hours two RAF Hornets flew over at about 5000 feet but did not see them. Five minutes later a RAF Valetta crew spotted them and recalled the Hornets for protection. About an hour later a flying boat turned up but high seas prevented it landing. Shortly after, a RAF York, an Air Vietnam Skymaster and a French Privateer joined the queue. Phil’s bloodied little band rejoiced that the recently murderous sky had become crammed with friends.

Several other stations monitoring the emergency frequency copied Stephen Wong’s distress message. One of these was Mum Louttit, the radio officer of a Cathay Pacific DC3 bound for Labuan. He advised his skipper and immediately contacted Kai Tak. The Senior Signals Officer confirmed he had received the SOS and that help was on the way. Mum kept a listening watch on the distress frequency, but no further calls came from the stricken airliner, for Steve Wong and the Skymaster had slipped into their watery grave.

In Hong Kong Pip Pickering calculated the wreck site from the Skymaster’s last reported point. He scrambled the two RAF Hornets assigned for search and rescue duties, and the position he gave the Hornets proved to be less than two miles in error.

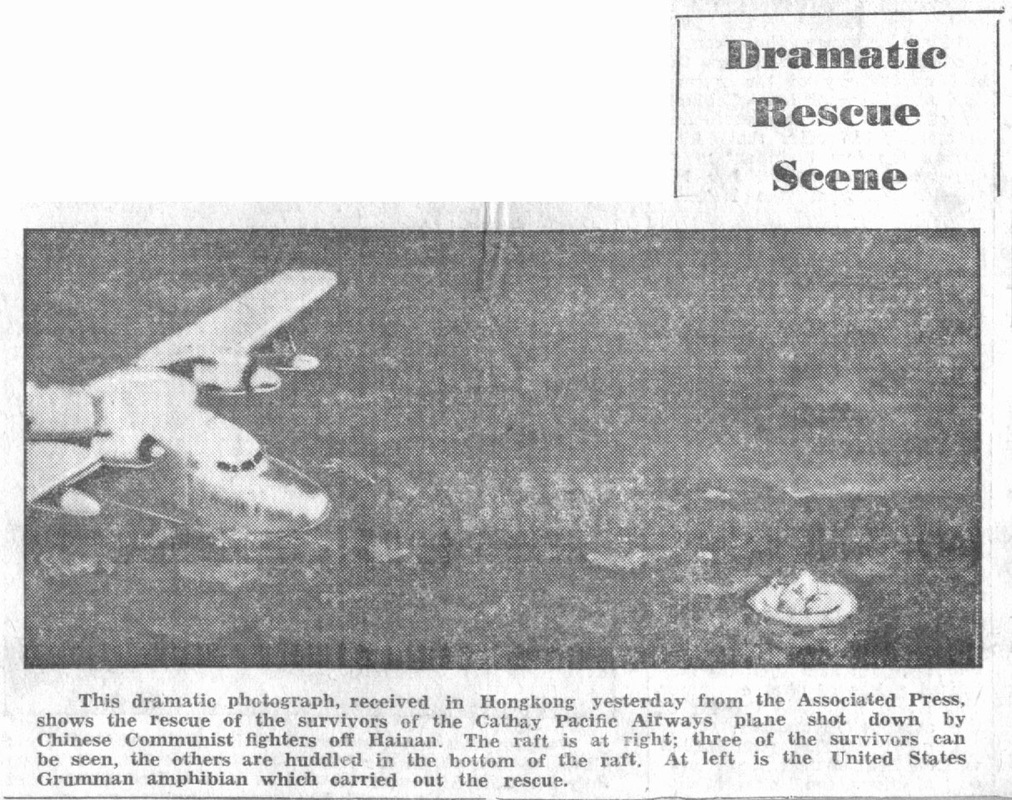

The 31st Air Rescue Squadron was then based at the U.S. Clarke Air Base, 50 miles north of Manila. The duty officer read Pip’s dramatic message that a British airliner had reported it was going down on fire. Pip calculated its position as 18.36N: 110.28E just to the south east of Hainan Island. The duty officer logged the message at 08:35 hours Philippine time - 09:35 hours Hong Kong time - and scrambled his two SA-16 amphibious Grumman Albatross planes.

Several other stations monitoring the emergency frequency copied Stephen Wong’s distress message. One of these was Mum Louttit, the radio officer of a Cathay Pacific DC3 bound for Labuan. He advised his skipper and immediately contacted Kai Tak. The Senior Signals Officer confirmed he had received the SOS and that help was on the way. Mum kept a listening watch on the distress frequency, but no further calls came from the stricken airliner, for Steve Wong and the Skymaster had slipped into their watery grave.

In Hong Kong Pip Pickering calculated the wreck site from the Skymaster’s last reported point. He scrambled the two RAF Hornets assigned for search and rescue duties, and the position he gave the Hornets proved to be less than two miles in error.

The 31st Air Rescue Squadron was then based at the U.S. Clarke Air Base, 50 miles north of Manila. The duty officer read Pip’s dramatic message that a British airliner had reported it was going down on fire. Pip calculated its position as 18.36N: 110.28E just to the south east of Hainan Island. The duty officer logged the message at 08:35 hours Philippine time - 09:35 hours Hong Kong time - and scrambled his two SA-16 amphibious Grumman Albatross planes.

Grumman AF-1009, commanded by Captain Jack Thompson Woodyard, was airborne 21 minutes after the Rescue Control Centre received the signal, and the second, AF-1018, under the command of Captain Dale R. Baker quickly followed.

Captain Woodyard’s crew comprised co-pilot Captain Tommy B. Arnold, and Navigator-Captain Albert F. Smith. Engineer Staff-Sergeant Douglas F. Blair, Radio Operator Laurence F. Rodriguez and Aero Medical Specialist Cecil R. Smith in support. Rodriguez and Smith were designated A/3C and A/2C respectively but there were no second or third class airmen on that crew that day, more like first-class plus.

Navigator Smith calculated a heading to bring the Albatross to a point midway between the last position and Hong Kong. When Kai Tak advised no further messages he revised his intercept 50 miles North East of the Skymaster’s last reported position. Captain Woodyard instructed Radio Operator Rodriguez to advise Captain Baker in 2 Dumbo 46 of the course alteration. Shortly afterwards Hong Kong advised that survivors were in a dinghy, and his original position would be close to the mark.

At 13:00 hours Rodriguez copied a message from Hong Kong, relayed from the Chinese People’s Government. The text prohibited any military aircraft from approaching the scene of the accident and to remain well clear of Hainan Island. Captain Woodyard told Rodriguez merely to acknowledge the message.

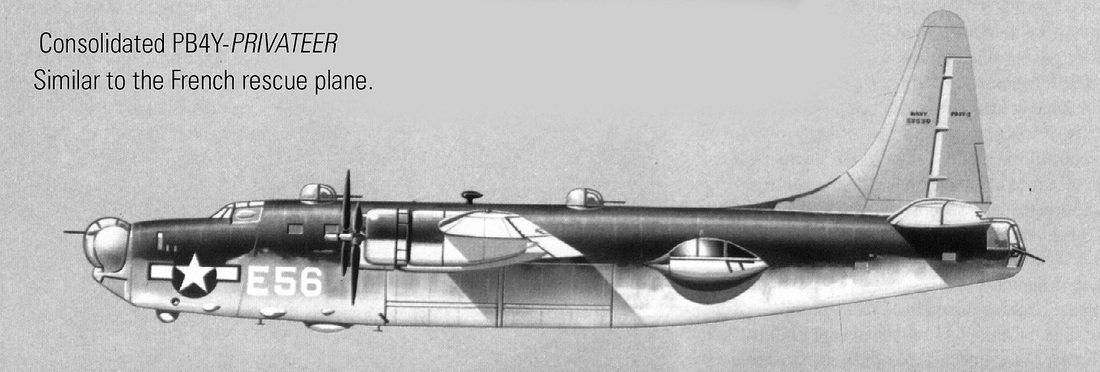

About 75 miles from the dinghy’s reported position Rodriguez established radio communication with a French Privateer aircraft on

121.5 mc. Its skipper reported he had clear visual contact with the dinghy and could provide full rescue gear if required. The Frenchman had received the distress call in Tourane (now Da Nang) and responded.

Captain Jack Woodyard descended to 1500 feet to stay below a layer of broken cloud, but at that height he could not spot the bobbing dinghy. The efficient Frenchman saw his dilemma and marked the dinghy with a drift signal and the Albatross crew saw it from about four miles away.

The calculation Woodyard had to make before the touchdown was complex. His landing must be so precise that the reversible propellers could bring the Albatross to a complete stop by the time the next wave-crest arrived. That day there was exactly 180 feet between crests. His report follows.

The sea appeared fairly rough, and confused by a groundswell system running 60 to 70 degrees to the main flow. I estimated eight to ten foot seas were running and the wind was southerly at twelve to fifteen knots.

We dropped two Mark 5-drift signals at the dinghy’s position. I positioned my plane to land three miles north of the dinghy off the southeast coast at Tai Chou Tau Island. In that area the ground-swell system was dampened.

121.5 mc. Its skipper reported he had clear visual contact with the dinghy and could provide full rescue gear if required. The Frenchman had received the distress call in Tourane (now Da Nang) and responded.

Captain Jack Woodyard descended to 1500 feet to stay below a layer of broken cloud, but at that height he could not spot the bobbing dinghy. The efficient Frenchman saw his dilemma and marked the dinghy with a drift signal and the Albatross crew saw it from about four miles away.

The calculation Woodyard had to make before the touchdown was complex. His landing must be so precise that the reversible propellers could bring the Albatross to a complete stop by the time the next wave-crest arrived. That day there was exactly 180 feet between crests. His report follows.

The sea appeared fairly rough, and confused by a groundswell system running 60 to 70 degrees to the main flow. I estimated eight to ten foot seas were running and the wind was southerly at twelve to fifteen knots.

We dropped two Mark 5-drift signals at the dinghy’s position. I positioned my plane to land three miles north of the dinghy off the southeast coast at Tai Chou Tau Island. In that area the ground-swell system was dampened.

We made the normal rough water landing heading 240 degrees. The ground swell crests were barely touched before stalling on the swell crest. This eliminated any problem from the ground swell. The sea conditions were close to my evaluation. However, after clearing the protection of the island taxiing was slowed considerably and on occasions the wing floats and pedestals were completely submerged. During periods of extreme roll when the props hit the water it became necessary to use idle reverse position to avoid straining or killing the engines.

The French Privateer guided me to the dinghy. As we approached it the engineer, posted in the bow, readied a throw-line. Meanwhile, the radio operator and the medic were stationed at the rear hatch with a throw-line and boathook. We circled to check the condition of the survivors and if they were capable of helping themselves. We made a successful single engine approach cutting the port engine before reaching the dinghy so that the prop would stop and position correctly

The French Privateer guided me to the dinghy. As we approached it the engineer, posted in the bow, readied a throw-line. Meanwhile, the radio operator and the medic were stationed at the rear hatch with a throw-line and boathook. We circled to check the condition of the survivors and if they were capable of helping themselves. We made a successful single engine approach cutting the port engine before reaching the dinghy so that the prop would stop and position correctly

We assisted 9 survivors aboard. The captain of the downed Skymaster came to the flight deck and stated ‘We were shot down. Watch out for yourselves. There may be other fighters in the area.’ I immediately called Captain Baker in 2 Dumbo 46, advised him of the number of survivors, and asked him to cross to the rescue frequency. When he established contact I cautioned him to watch for bandits.

I continued taxiing back to where we had landed. Meanwhile, Captain Arnold and airman Rodriguez were struggling to hang the Jato (jet assisted take off) units. After much exertion they got the port Jato into position but couldn’t manage the bulky starboard one. Captain Arnold came to the flight deck and advised they had to have a short rest. As he panted our cover aircraft reported the approach of a formation of unidentified planes. With an oath he rushed away and positioned the massive bottle unaided.

As we neared the shoreline uniformed men could be seen running for berthed fishing boats. I turned into wind about a hundred yards from them. With the additional weight I needed all the smoother water available.

We had no difficulty with the take-off, gently easing 110 degrees to port during the first part of the run. This gave us full effective power on both engines by the time the aircraft straightened out on heading. Control and attitude response was obtained before firing the Jato units. I nursed the plane over three major crests before we could climb away. Safely in the air, we learned the approaching formation was friendly U.S.N. Skyraiders.

As the Albatross became airborne Captain Cos Cosgrove arrived on the scene in a Catalina with Captain Pat Armstrong as his first officer. The other member of his crew was a youthful Ambrose Tai, who at that time had no official qualifications. Pat, of course, was a natural and Cos shanghaied him without a qualm. Pat had reported to Kai Tak to command the Skymaster on its next schedule.

Captain Baker now advised all the planes flying cover how the innocent Skymaster had met its fate. He suggested that as there were no more survivors they get the hell out of there!

The pilot of the French Privateer was the least understanding. The other commanders tried to reason with him but he had worked himself into an uncontrollable rage. His voice screeched across the airwaves that he needed no advice from anyone. With a roar, that needed little amplification, he advised the world he had the armament, and the will, to wipe out the entire fornicating Communist Chinese Air Force. Almost on bended knee he pleaded for the petite chance to prove it! The site commander Captain Woodyard thanked him for his invaluable help, then stood him down. With the Frenchman’s au-revoir ringing in their ears the cover planes tucked themselves around the survivors’ plane and brought them home.

At precisely 17:15 hours by Cedric Carlton’s robust watch, Captain Woodyard feathered the Albatross onto Kai Tak’s runway.

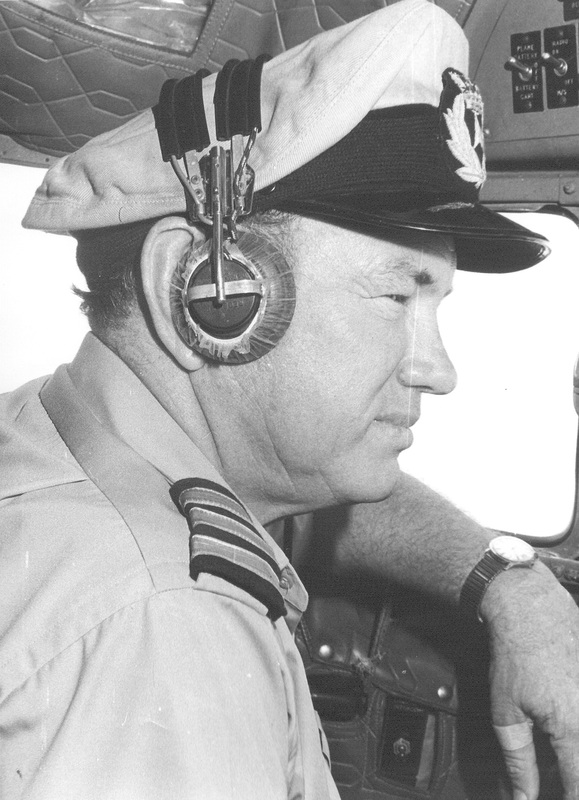

Capt. Jack Woodyard follows the Marshall’s Bats, Kai Tak Airport.

I continued taxiing back to where we had landed. Meanwhile, Captain Arnold and airman Rodriguez were struggling to hang the Jato (jet assisted take off) units. After much exertion they got the port Jato into position but couldn’t manage the bulky starboard one. Captain Arnold came to the flight deck and advised they had to have a short rest. As he panted our cover aircraft reported the approach of a formation of unidentified planes. With an oath he rushed away and positioned the massive bottle unaided.

As we neared the shoreline uniformed men could be seen running for berthed fishing boats. I turned into wind about a hundred yards from them. With the additional weight I needed all the smoother water available.

We had no difficulty with the take-off, gently easing 110 degrees to port during the first part of the run. This gave us full effective power on both engines by the time the aircraft straightened out on heading. Control and attitude response was obtained before firing the Jato units. I nursed the plane over three major crests before we could climb away. Safely in the air, we learned the approaching formation was friendly U.S.N. Skyraiders.

As the Albatross became airborne Captain Cos Cosgrove arrived on the scene in a Catalina with Captain Pat Armstrong as his first officer. The other member of his crew was a youthful Ambrose Tai, who at that time had no official qualifications. Pat, of course, was a natural and Cos shanghaied him without a qualm. Pat had reported to Kai Tak to command the Skymaster on its next schedule.

Captain Baker now advised all the planes flying cover how the innocent Skymaster had met its fate. He suggested that as there were no more survivors they get the hell out of there!

The pilot of the French Privateer was the least understanding. The other commanders tried to reason with him but he had worked himself into an uncontrollable rage. His voice screeched across the airwaves that he needed no advice from anyone. With a roar, that needed little amplification, he advised the world he had the armament, and the will, to wipe out the entire fornicating Communist Chinese Air Force. Almost on bended knee he pleaded for the petite chance to prove it! The site commander Captain Woodyard thanked him for his invaluable help, then stood him down. With the Frenchman’s au-revoir ringing in their ears the cover planes tucked themselves around the survivors’ plane and brought them home.

At precisely 17:15 hours by Cedric Carlton’s robust watch, Captain Woodyard feathered the Albatross onto Kai Tak’s runway.

Capt. Jack Woodyard follows the Marshall’s Bats, Kai Tak Airport.

Their joy in a safe arrival was tempered with sorrow for those who had lost their lives. Miss Rita Cheung had died within sight of Hong Kong and now lay in a tiny rag-doll bundle covered with the medic’s flying jacket. Although Rodriguez had transmitted a list of survivors, only a handful of those gathered at the airport knew who they were. The cries were heart-rending when Captain Woodyard announced, with a sob in his voice, there was nobody else.

A couple of hours earlier the Kowloon Hospital had received a directive to stand by for an emergency. Tired doctors and nurses who had treated scores of victims from a disastrous fire that had devastated Kowloon Tsai were back on duty.

As the evening wore on Tom Bax, Cathay’s Traffic Manager came to comfort the survivors. While they were reliving the shooting down Cedric mentioned he had a stinging pain under his right arm. Tom gently lifted the arm and saw a bullet had passed right through the fleshy part.

Cedric then speculated that the bullet that passed through his arm was likely the one that first killed George Cattanach, for the instant he felt that bee-sting George had gasped and crumbled in the aisle.

Then with great amusement Cedric showed Tom his right wrist carefully taped to take care of a non-existent sprain, while his ignored ankle resembled a well-nourished football.

In the next bed, Mr Lui, had received treatment for a non-existent sprained ankle. While his right wrist lay above the sheet the size of a prize winning grapefruit.

A weary matron asked Cedric, Have you had a bowel movement today? When he answered, Not voluntarily she missed his glibness and ordered an enema.

At Labuan a group of friends held a wake for Cedric. Mum Louttit, who had recorded the initial distress message, stayed crouched over his radio until they reached Labuan. Prior to landing he copied a list of survivors and Cedric’s name did not appear on that list. The mistake arose when Rodriguez passed a sheet of paper around for the survivors to write their name. Mr Lui Luen-fong recorded his name and his alias. Rodriguez counted nine names and transmitted the list.

Captain McKenzie, a close friend of Cedric’s from their early flying days met the DC3 at Labuan. When McKenzie heard that Cedric was not on the list he organised a wake.

It continued all night, becoming happier with each passing hour and producing some fragile heads the next day. The skipper tried to get an hour’s sleep but complained the flies kept walking on the ceiling in cast-iron boots.

Cathay Pacific never knew their crew went from Cedric Carlton’s wake to their DC3, although the staid Hong Kong Director of Civil Aviation knew but did not care! Apparently, their condition did not effect their performance, and some of the regular oil company passengers remarked on the unusually smooth landings, then making lifelong enemies of the skipper and co-pilot when they asked if the radio officer did the flying!

When they arrived in Hong Kong they learned that Cedric was hale and hearty. Although their wake had been in vain, what a great piss-up they had!

The next few days produced speculation and theories about the cause of the aerial murder. Some were mundane and eminently forgettable, but here is the one that most appealed to me.

The warlords of Taiwan, smarting at the expulsion from their Homeland, needed an incident. It should be a simple type of incident plausible to a world tired of war, but one that would bring immediate aid from a powerful friend.

Taiwan intelligence decided on the destruction of a military Curtiss Commando C46 aeroplane by Chinese fighters. Aboard would be a full load of volunteers dressed in the full trappings of high rank officers attending a conference in Bangkok.

The shooting down must be close to a Chinese coastline, yet in International Waters and before the onset of the Continental Shelf. This would allow salvage operations if things got that far. The salvage would determine the bodies were indeed officers of substance.

The eastern coast of Hainan Island was the perfect location, and furthermore, it had an approved Airways lane nearby. With their plans at an advanced stage Taiwan leaked the information to the Communist Chinese. The target was mouth watering – to wipe out most of the Taiwan general staff must not be missed!

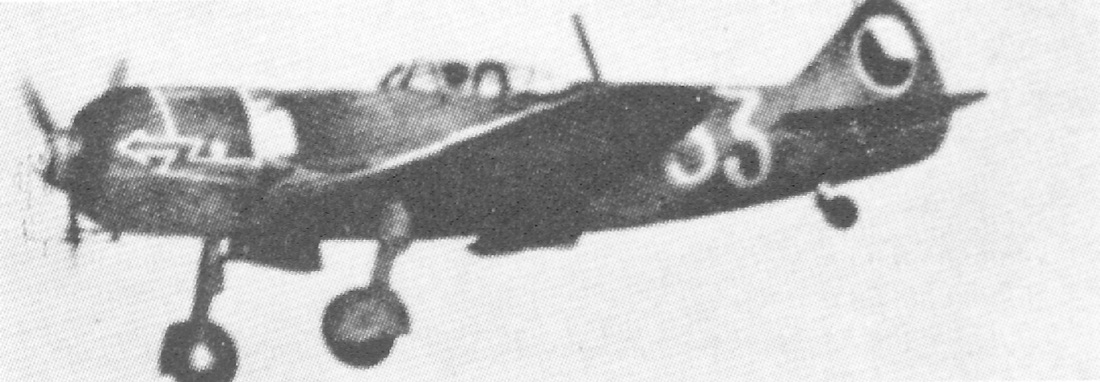

On the morning of 23 July 1954 the Curtiss Commando left Taipei. About one hour later it had an engine failure and was forced to return to base. Meanwhile, Cathay’s Skymaster, after its early mechanical delays, lumbered along in majestic dignity. At the calculated intercept point Communist Lavochin La 7 Soviet-built prop-driven fighters lurked. They swooped on their expected Curtiss Commando and blasted it into oblivion.

This is a far-fetched story, however during World War 2 far less plausible schemes were tried with occasional success. Whatever the reason, one is left pondering whether the sacrifice of the Cathay Pacific Airways Skymaster and its innocent passengers prevented World War 3? It is possible, for an event seventy-two hours later indicates a launching platform was positioned for material confrontation.

|

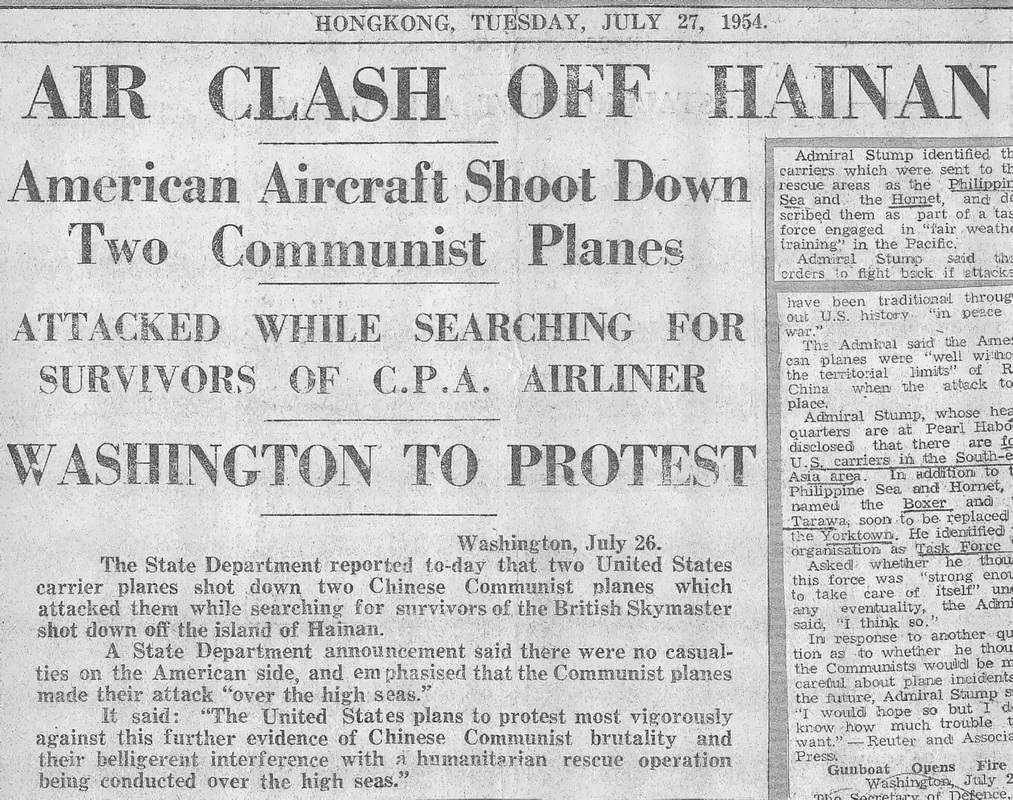

Others shared the Frenchman’s desire for a fight, and on 26 July Washington advised the press of an air battle between American and Communist Chinese planes. The action took place in International Waters off the eastern coast of Hainan Island. Admiral Felix Stump, told a news conference on 27 July, his instructions were simple. Give cover to the searchers, but if a hostile pass was made be quick on the trigger. Admiral Stump, whose headquarters are at Pearl Harbour, identified the carriers in the search area as the Philippine Sea and the Hornet. As the search progressed a 3 minute air-battle off the coast of Hainan Island resulted in his planes splashing two Chinese La 7s. The first met its end under the guns of Lieutenant Roy Tatham and Ensign Richard Crooks. Neither man had faced battle before. The second found it had fallen into a nest of hornets. The combined firepower of six Skyraiders and a Corsair blasted it to wreckage, and neither Chinese pilot hit the silk. In righteous indignation, Peking Radio announced that two American fighter planes had made piratical attacks on two Polish merchant ships and one Chinese escort vessel. They made no mention of the loss of their La 7 fighter planes. |

The politicians had a field day with Mr Anthony Eden the British Foreign Secretary using the words savage and inexcusable. A reporter goaded Mr Clement Attlee, Leader of the Labour Opposition, to say absolutely inexcusable. He would go no further for he planned on visiting Communist China the following month. Both these courageous men of words allowed themselves mollified by Peking’s regret and willingness to pay compensation. Peking’s acceptance of blame allowed a businessman to change his mind. He felt an eased conscience with its crocodile-tears apology, so now he could reopen negotiations on a trade deal he had cancelled the day before. His change of mind statement was a dubious gem - it would be immoral to do business with people who shot down your planes.

The Governor of Hong Kong, Sir Alexander W.G.H. Grantham GCMG, sent a congratulatory cable to Major-General John W. Sessumus Jnr., in which he expressed his highest praise for the professionalism of the rescue crew of the downed Cathay plane.

The Colonial Secretary, Robert Brown Black GMG, OBE emulated the Governor’s words on behalf of the people of the Crown Colony.

The Commander Air Sea Rescue Service at Orlando A.E.B., Florida received Colonel E. Horras’s report of the incident. In it he made the following recommendations. In order to give personal recognition for a job well done, Captain Woodyard and his crew have been recommended for the Distinguished Flying Cross. Captain Baker and Captain Veith of the second crew have also been recommended for the DFC. The remainder of Captain Baker’s crew has been recommended for the Air Medal.

Cathay Pacific remembered Captain Woodyard at Christmas in 1954 by presenting him with a salver engraved, To Captain Jack Thompson Woodyard, USAF. In grateful recognition of his gallantry in SA-16, No. AF1009 off Hainan Island, July 23, 1954.

The sabre rattling gradually subsided and the media lost interest. Their sole reference was that BOAC had re-routed their aircraft further east of Hainan’s coastline.

However, men who value deeds ahead of words worked behind the scenes to bring due credit to other heroes of that murderous attack.

Mr Julian F. Harrington the American Consul General in Hong Kong wrote to Cathay Pacific’s Chairman Mr. J. A. Blackwood. This letter, dated 30 July expressed regret that so little had been said of the heroism of the airliner’s crew and the skilful handling of the crippled plane by Captain Blown.

Without the successful ditching, he wrote, there would have been no survivors to rescue.

The Governor of Hong Kong, Sir Alexander W.G.H. Grantham GCMG, sent a congratulatory cable to Major-General John W. Sessumus Jnr., in which he expressed his highest praise for the professionalism of the rescue crew of the downed Cathay plane.

The Colonial Secretary, Robert Brown Black GMG, OBE emulated the Governor’s words on behalf of the people of the Crown Colony.

The Commander Air Sea Rescue Service at Orlando A.E.B., Florida received Colonel E. Horras’s report of the incident. In it he made the following recommendations. In order to give personal recognition for a job well done, Captain Woodyard and his crew have been recommended for the Distinguished Flying Cross. Captain Baker and Captain Veith of the second crew have also been recommended for the DFC. The remainder of Captain Baker’s crew has been recommended for the Air Medal.

Cathay Pacific remembered Captain Woodyard at Christmas in 1954 by presenting him with a salver engraved, To Captain Jack Thompson Woodyard, USAF. In grateful recognition of his gallantry in SA-16, No. AF1009 off Hainan Island, July 23, 1954.

The sabre rattling gradually subsided and the media lost interest. Their sole reference was that BOAC had re-routed their aircraft further east of Hainan’s coastline.

However, men who value deeds ahead of words worked behind the scenes to bring due credit to other heroes of that murderous attack.

Mr Julian F. Harrington the American Consul General in Hong Kong wrote to Cathay Pacific’s Chairman Mr. J. A. Blackwood. This letter, dated 30 July expressed regret that so little had been said of the heroism of the airliner’s crew and the skilful handling of the crippled plane by Captain Blown.

Without the successful ditching, he wrote, there would have been no survivors to rescue.

|

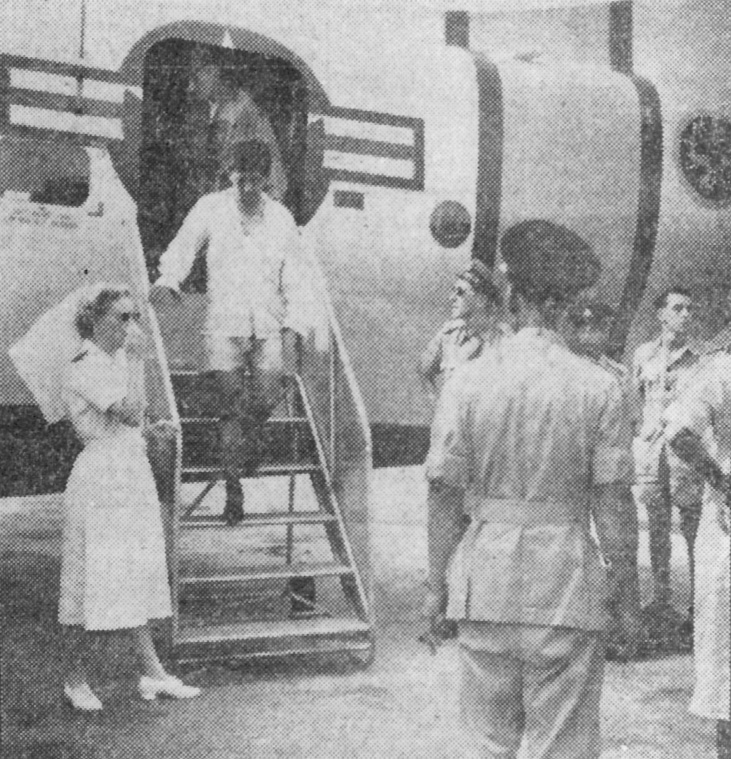

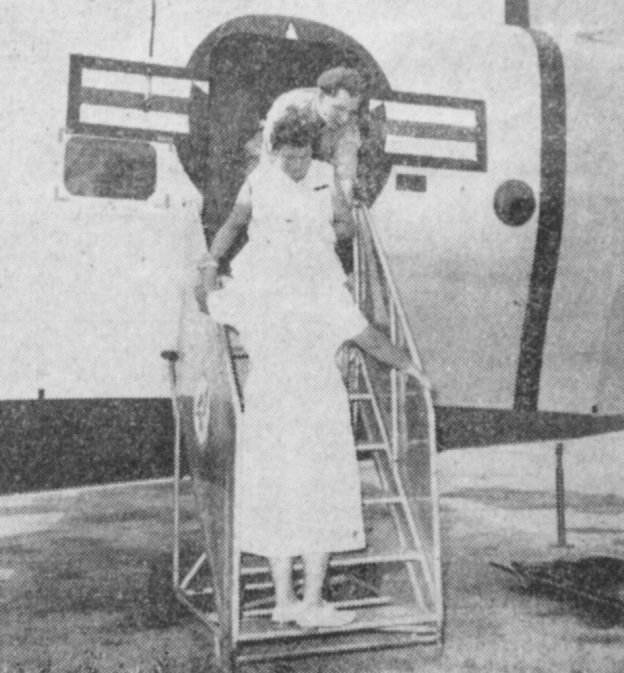

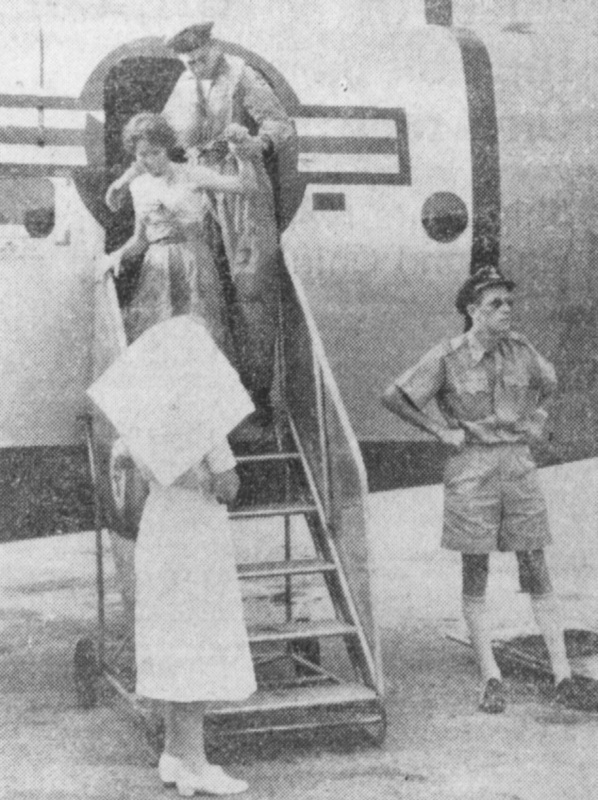

Captains Courageous On 15 June 1955, His Excellency the Governor, Sir Alexander Grantham pinned the Badge of the Queen’s Commendation For Valuable Service in the Air on Captains Philip Blown (Left picture) and Cedric Windas Carlton. (Right picture) (Bottom Picture) L to R: Capt. Ced Carlton, His Excellency, Miss Irene Ross, Cedric’s fiancee, Mrs Bunty Blown, and Capt. Phil Blown. |

The Captain

Phil Blown was born in Tientsin, China in 1913. During the war he saw service in New Guinea as a Flight Lieutenant in the RAAF. He joined Cathay Pacific in 1948 and held the position of Chief Pilot from December 1952 until he resigned ten years later. Phil and his wife Bunty retired to live

in Sydney.

The Co-Pilot

Born in Brisbane in 1921, Cedric Carlton served with the RAAF in New Guinea and other stations in Australia. His posting to Darwin brought him into contact with the legendary air ace Squadron Leader Keith Bluey Truscott, DFC and bar.

Cedric served with Cathay Pacific from 1948 to 1951 and again from 1953 to 1964. On Saturday 15 August 1959, at Hong Kong’s St. John’s Cathedral, Miss Irene Deane Ross became his bride.

In 1964, during a routine Flying Licence renewal, the medical examiner detected a slight diabetic condition. Assessed as medically unfit the Hong Kong DCA suspended his Commercial Flying Licence.

The National and General Life Assurance Company of Teddington, London refused to honour his crew disablement insurance policy. The company based its refusal on the mildness of his condition as one easily controlled by a low carbohydrate diet. So it considered the Department erred by withdrawing the licence. However, the Department stood its ground and he had lost his livelihood.

Cedric brought legal proceedings against the powerful Assurance Company. In 1966 the Court found in Cedric’s favour. After two years he finally collected his $HK20,000 under a crew disablement insurance policy.

Irene and Cedric retired to Queensland. He died in July 1992.

The Aeroplane

A Douglas DC4 (C54B) Skymaster was previously registered PH-TLO. Cathay Pacific Airways purchased her from K.L.M. on 7 September 1949 for $HK-803,800 -and VR-HEU became her Hong Kong Registration.

She entered CX service in late September 1949 and carried 47,399 passengers over 15,279 flying hours under its flag.

|

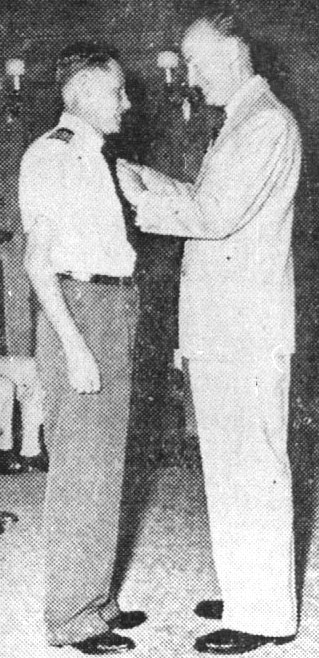

Left: Clarke Air Force Base, Philippine Islands 26 August 1954. Maj.Gen. John W. Sessumus Jr., pins the Distinguished Flying Cross on Captain Jack T. Woodyard for his part in rescuing nine survivors from a Cathay Pacific Airliner near Hainan Island on 23 July, 1954.The General’s aide, Capt. Frank Rohan, looks on. |

The compensation

The J.K. Swire diarist recorded.

Cathay Pacific submitted a claim for £251,400 as compensation. At the end of November 1954 the Chinese Government paid that amount in full to Her Majesty’s Government. Cathay Pacific received an on account payment of 175,000 pounds sterling.’

The Diarist added.

I fear a stiff fight with the Claims Commission for the balance.

His fears proved correct, for the company waited until August 1955 for the balance. This made a total paid of £268,560, £17,160 more than the original claim. Bureaucracy moves in strange ways, but perhaps the balance had earned interest!

Conclusion

Of the many tributes showered on the rescuers, the one that stays in mind is that from Mr John Thorburn, husband of a survivor. After giving the highest praise to Captain Blown and his crew he addressed General Sessums.

Would you convey to Captain Woodyard and his men my heartfelt thanks for all they had done `to bring my wife back to me and her babies.’

The J.K. Swire diarist recorded.

Cathay Pacific submitted a claim for £251,400 as compensation. At the end of November 1954 the Chinese Government paid that amount in full to Her Majesty’s Government. Cathay Pacific received an on account payment of 175,000 pounds sterling.’

The Diarist added.

I fear a stiff fight with the Claims Commission for the balance.

His fears proved correct, for the company waited until August 1955 for the balance. This made a total paid of £268,560, £17,160 more than the original claim. Bureaucracy moves in strange ways, but perhaps the balance had earned interest!

Conclusion

Of the many tributes showered on the rescuers, the one that stays in mind is that from Mr John Thorburn, husband of a survivor. After giving the highest praise to Captain Blown and his crew he addressed General Sessums.

Would you convey to Captain Woodyard and his men my heartfelt thanks for all they had done `to bring my wife back to me and her babies.’

Hainan – Deja Vu

On April Fool’s Day 2001 a US EP-3A surveillance aircraft and a Chinese F-8 jet fighter collided close to where Cathay’s Skymaster met her end.

The Chinese pilot Wang Wei parachuted from his stricken plane. An extensive search never found his body.

The damaged EP-3A landed without permission on Hainan Island where the People’s Liberation Army arrested the crew of 21 males and 3 females.

After several days of friendly questioning all 24 crewmembers were released. Some of the crew sported black eyes and bruised lips as a result of walking into doors!

The EP-3A remained in Chinese hands for many weeks until the Americans were finally allowed to dismantle their aircraft when a giant Russian cargo plane flew out her parts.

The Chinese hierarchy had saved face!

On April Fool’s Day 2001 a US EP-3A surveillance aircraft and a Chinese F-8 jet fighter collided close to where Cathay’s Skymaster met her end.

The Chinese pilot Wang Wei parachuted from his stricken plane. An extensive search never found his body.

The damaged EP-3A landed without permission on Hainan Island where the People’s Liberation Army arrested the crew of 21 males and 3 females.

After several days of friendly questioning all 24 crewmembers were released. Some of the crew sported black eyes and bruised lips as a result of walking into doors!

The EP-3A remained in Chinese hands for many weeks until the Americans were finally allowed to dismantle their aircraft when a giant Russian cargo plane flew out her parts.

The Chinese hierarchy had saved face!