Merchant Navy

(Plus Scary First Solo Flight)

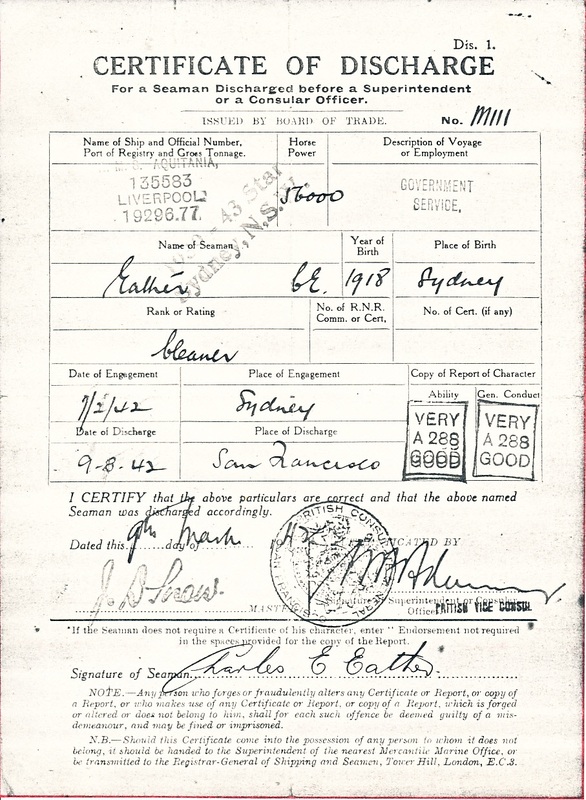

During May 1940 I enlisted with the lst Australian Anti-Aircraft Regiment and became Gunner Eather NX 17877. My term was brief; intervention of some sort or other led to my discharge - "not occasioned by his own default". The following January, not at all discouraged, I decided I would still be of combative value to my country and joined the Merchant Navy.

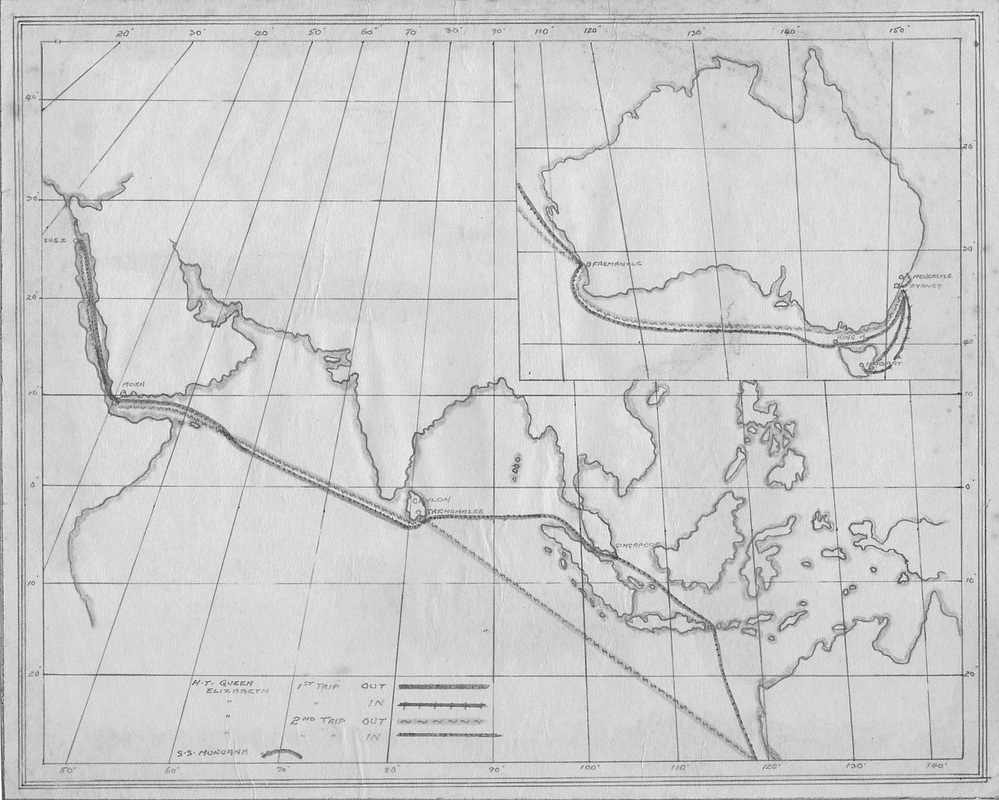

My first trip was on S.S. Mungana, a 3315-ton rust-bucket that set out on the seventy-mile trip from Sydney to Newcastle one night in February. She was so unseaworthy that what should have been a routine passage of a few hours developed into a nightmare of forty-eight. Her rudder fell off outside Newcastle and we wallowed round in mountainous seas until a tug came to drag us into port. The tug was delayed because the boom was closed following the bombardment of any enemy ship that had tried to slip out of harbour in a fruitless attempt to break her internment. I'd had enough of Mungana, but the experience had one good result. I had been so seasick that never again was I sick at sea or in the air.

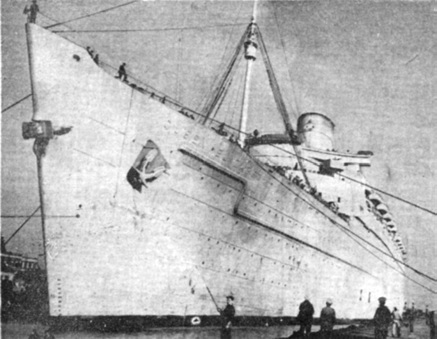

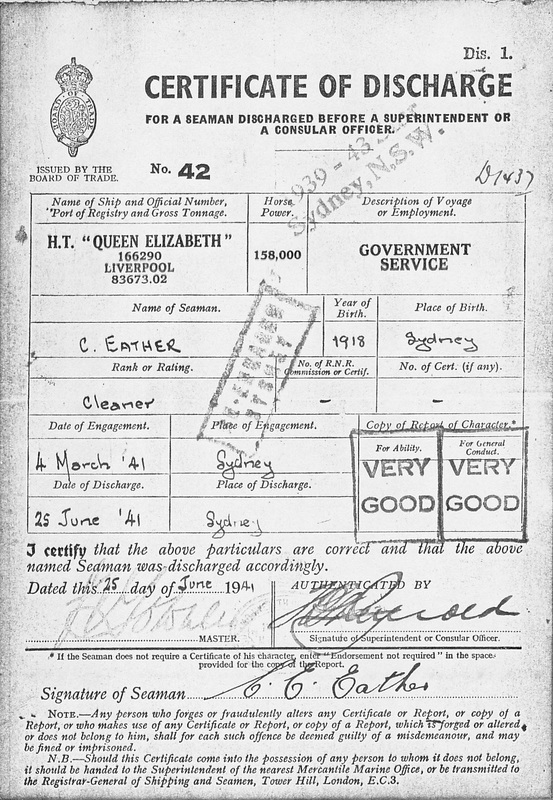

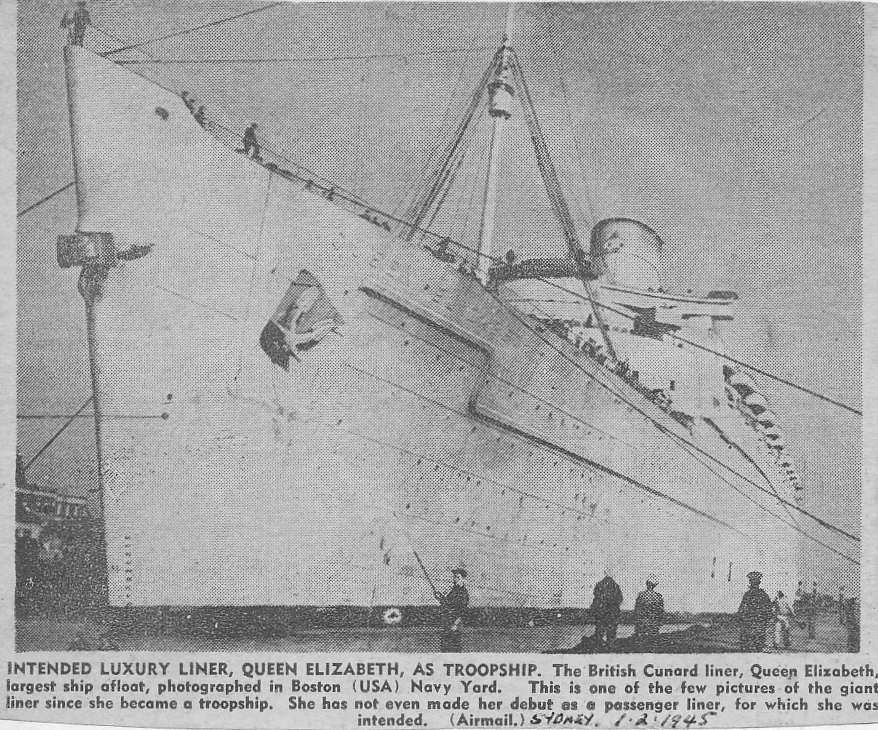

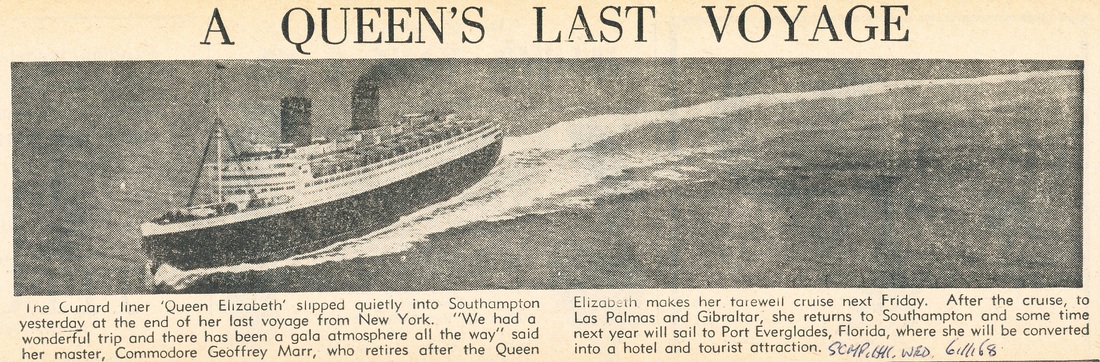

Next month, March 194l, I signed articles on HT Queen Elizabeth, then the largest ship in the world, and I recall her with affection. Her turn of speed was absolutely phenomenal, and it earned my heartfelt thanks when we cleared the Suez port of Taufiq (Tewfik) in a hurry because of an impending bombing raid on Alexandria. Returning from Suez, when we crossed the Great Australian Bight the seas were so mountainous that the after gun-deck was untenable. Though it was more than seventy feet above Plimsoll line the seas broke right over it.

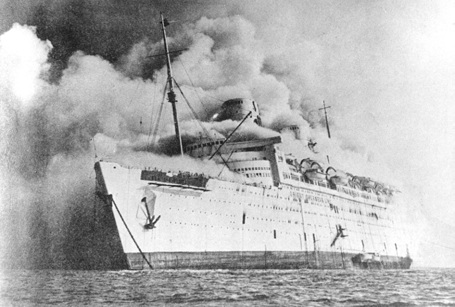

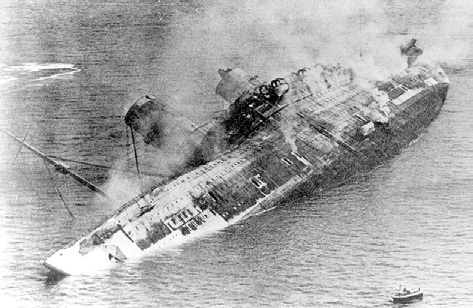

I walked from stem to stern under the keel of that massive vessel later, when she was in dry dock at Singapore. Finally on a Sunday morning, January 19,1972 I saw the beautiful ship, now rechristened Seawise University and registered at Panama, racked by explosions and consumed by spreading flames in Hong Kong's western harbour. Her blackened hulk remains there to this day, a mass of useless metal.

I signed off the QE on June 25, 1941, and the very next day found me belted into the cockpit of a DH 60 Gipsy Moth (VH-UFV) with craggy-faced Howard K. Morris patiently demonstrating how to fly it straight and level. On a day in August, after I had piled up six hours and ten minutes instruction he climbed out of his seat, removed the forward control stick and, tucking it under his arm, stalked away, saying over his shoulder, "Off you go".

I did, and managed a really good first solo. Immediately anyone set out on his first solo those days, an unwritten rule stopped the operation of the whole airfield until the tyro had concluded this once-in-a-lifetime experience. As I rolled to a stop Howard K was leaning against a Tiger Moth just off to the right, talking to the Air Force instructor who was holding his machine with the prop just ticking over. He bounded across to me with a beaming grin and told me, 'Do another circuit'- something he had never done before, or since, probably. This time I made every mistake in the book, and still wonder that I got through without damaging myself or the Gipsy. The silence from Howard on my return could have been cut with a knife, and we left the scene followed by ungentlemenly guffaws from the RAAF instructor.

As with all private ventures in wartime our fuel supply was limited. This retarded the building up of flying hours in pursuit of the elusive 'B' Commercial licence, the Open Sesame to a job. To get round this we used to introduce new members to the Royal Aero Club of New South Wales. On joining they became entitled to a fuel allowance - so it was important to canvass only those who didn't want to take flying instruction, and our ingenuity knew no bounds in locating candidates for membership who would pass on their share of the priceless gravy. Two of the several new members I brought in were Chinese sisters named Bow, who raised the eyebrows of the selection committee when they listed their occupations as 'champagne bottle turners'.

We tapped another source of fuel supply by flying Army co-operation exercises to give gun-laying and predictor practice to anti-aircraft units at Bantry Bay and Lurline Bay on Sydney Harbour's North Shore. We pilots still had to pay for the hire of the aircraft but the fuel allowance meant we could build up our flying hours towards the coveted licence.

My old friend Bob Smith recalls those flights with amusement. We were supposed to fly over the batteries straight and level at about 5000 or 6000 feet but occasionally we would vary this with aerobatics and upset the predictor readings. Then the telephone would run hot with protests of righteous indignation and the dark threat of fuel withdrawal would bring us back to the straight and narrow. When I asked how they would handle the situation if any enemy aircraft did in fact follow an aerobatic course, I met a stony silence.

In this period I had been accepted for the RAAF Reserve, presented with a lapel badge and an instructional booklet and told to report three nights a week to nearby Newington College for technical lectures. I found the evenings very enjoyable and learned a lot from my instructors. The course stood me in good stead when I finally sat the examination for my 'B' licence. But the inactivity of the intervening periods was driving me to distraction and I decided to make another trip on my Merchant Navy papers. My RAAF Reserve status precluded this, but I rationalized that I wouldn't be missed for a few weeks. I was only kicking up my heels waiting for that Air Force call-up, and nothing appeared to be happening even though the Nips had entered the fray.

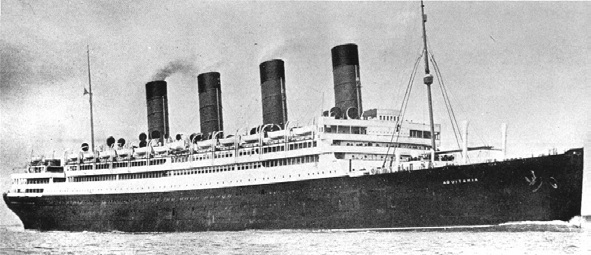

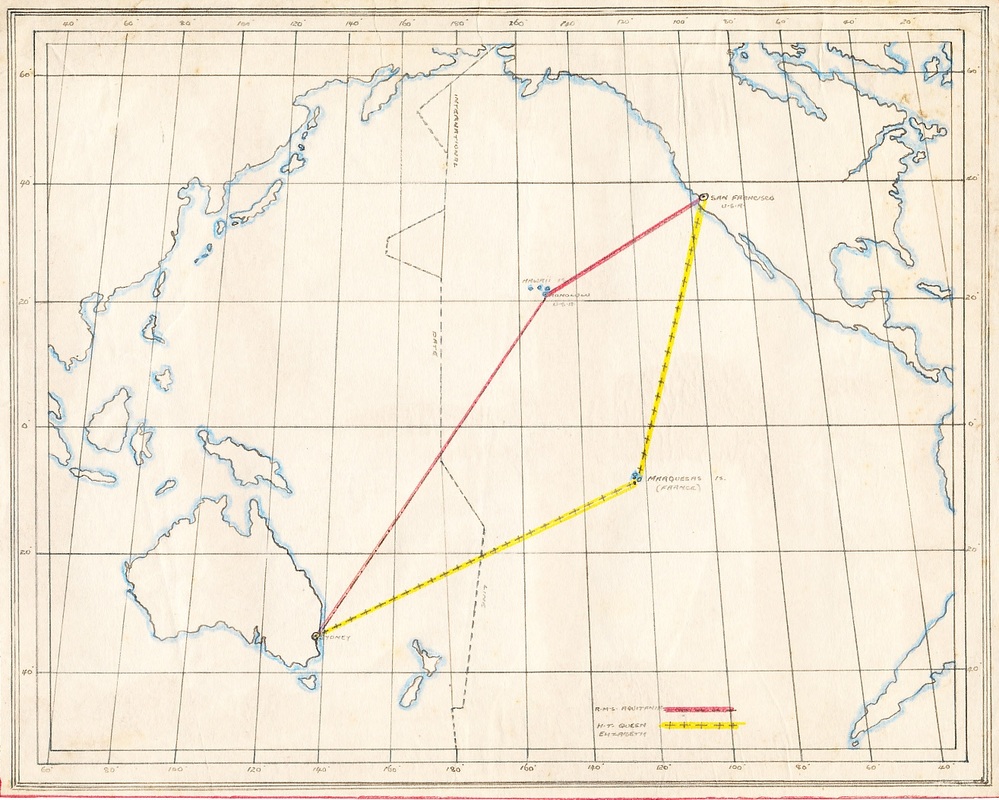

So in February 1942 I was aboard RMS Aquitania when she cleared Sydney Heads, and spent two Fridays the thirteenth dodging enemy subs. One of those thirteenths still haunts me. We ploughed through a vast area of wreckage. There were swollen bodies and, I fear, some which still contained a spark of life. Their weak but joyous calls turned to curses as we made no attempt to slacken speed and pick them up. Stopping to pick up survivors was just what the murderers skulking beneath the placid surface would be hoping for us to do; we would have been sitting ducks. But that knowledge was poor compensation for us, and none for them.

I signed off the QE on June 25, 1941, and the very next day found me belted into the cockpit of a DH 60 Gipsy Moth (VH-UFV) with craggy-faced Howard K. Morris patiently demonstrating how to fly it straight and level. On a day in August, after I had piled up six hours and ten minutes instruction he climbed out of his seat, removed the forward control stick and, tucking it under his arm, stalked away, saying over his shoulder, "Off you go".

I did, and managed a really good first solo. Immediately anyone set out on his first solo those days, an unwritten rule stopped the operation of the whole airfield until the tyro had concluded this once-in-a-lifetime experience. As I rolled to a stop Howard K was leaning against a Tiger Moth just off to the right, talking to the Air Force instructor who was holding his machine with the prop just ticking over. He bounded across to me with a beaming grin and told me, 'Do another circuit'- something he had never done before, or since, probably. This time I made every mistake in the book, and still wonder that I got through without damaging myself or the Gipsy. The silence from Howard on my return could have been cut with a knife, and we left the scene followed by ungentlemenly guffaws from the RAAF instructor.

As with all private ventures in wartime our fuel supply was limited. This retarded the building up of flying hours in pursuit of the elusive 'B' Commercial licence, the Open Sesame to a job. To get round this we used to introduce new members to the Royal Aero Club of New South Wales. On joining they became entitled to a fuel allowance - so it was important to canvass only those who didn't want to take flying instruction, and our ingenuity knew no bounds in locating candidates for membership who would pass on their share of the priceless gravy. Two of the several new members I brought in were Chinese sisters named Bow, who raised the eyebrows of the selection committee when they listed their occupations as 'champagne bottle turners'.

We tapped another source of fuel supply by flying Army co-operation exercises to give gun-laying and predictor practice to anti-aircraft units at Bantry Bay and Lurline Bay on Sydney Harbour's North Shore. We pilots still had to pay for the hire of the aircraft but the fuel allowance meant we could build up our flying hours towards the coveted licence.

My old friend Bob Smith recalls those flights with amusement. We were supposed to fly over the batteries straight and level at about 5000 or 6000 feet but occasionally we would vary this with aerobatics and upset the predictor readings. Then the telephone would run hot with protests of righteous indignation and the dark threat of fuel withdrawal would bring us back to the straight and narrow. When I asked how they would handle the situation if any enemy aircraft did in fact follow an aerobatic course, I met a stony silence.

In this period I had been accepted for the RAAF Reserve, presented with a lapel badge and an instructional booklet and told to report three nights a week to nearby Newington College for technical lectures. I found the evenings very enjoyable and learned a lot from my instructors. The course stood me in good stead when I finally sat the examination for my 'B' licence. But the inactivity of the intervening periods was driving me to distraction and I decided to make another trip on my Merchant Navy papers. My RAAF Reserve status precluded this, but I rationalized that I wouldn't be missed for a few weeks. I was only kicking up my heels waiting for that Air Force call-up, and nothing appeared to be happening even though the Nips had entered the fray.

So in February 1942 I was aboard RMS Aquitania when she cleared Sydney Heads, and spent two Fridays the thirteenth dodging enemy subs. One of those thirteenths still haunts me. We ploughed through a vast area of wreckage. There were swollen bodies and, I fear, some which still contained a spark of life. Their weak but joyous calls turned to curses as we made no attempt to slacken speed and pick them up. Stopping to pick up survivors was just what the murderers skulking beneath the placid surface would be hoping for us to do; we would have been sitting ducks. But that knowledge was poor compensation for us, and none for them.

We entered Honolulu's Pearl Harbour, littered with mute evidence of the infamous Japanese attack. After a quick shore leave we found that our task was to transport some 2000 American women and their children to the mainland. The sex which was offered and enthusiastically accepted throughout the run to San Francisco was out of this world. I know of few who missed out, and no difficulty arose until an inexperienced helmsman, whose mind was on far more pleasurable occupations proceeded to turn to starboard instead of to port in response to the blast that signalled the convoy to take a zig-zag sub avoidance. Fortunately no real damage resulted from the near collision. I think we lost a little paint off the starboard bow, but this did lead to a restriction of nocturnal pleasures. Probably just as well, for only the most agile could negotiate the deck and avoid the copulating couples occupying every nook and cranny.

At San Francisco we learned that certain irregularities existed in the articles we had signed, and it became necessary for each crew member to sign off and, if he wished, to sign new articles. I accepted this as an opportunity to leave the ship legally, and put into train a scheme to sneak across the border into Canada and there offer myself to the British Air Transport Command.

The British Consul could offer little advice on joining this command from American soil, but did say many others had followed my proposed route and were now doing sterling service flying replacement aircraft to the British Isles. It was a great pity Bob Buckby, another old mate of mine did not follow this path. He joined a refrigeration ship in Sydney which was "bumped" in the Atlantic, with the result that both his legs had to be amputated due to frostbite. I recall going aboard with him while this ship was alongside the Pyrmont wharves in Sydney, and she had death written all over her. When I expressed these fears Bob showed not the slightest interest.

As I sneaked up to the Canadian border a giant American cop grabbed me, gave me a couple of vigorous shakes and marched me off to the local bastille. He mellowed when I explained my reasons for being at the border, but not sufficiently to close his eyes to his duty. Next morning found me standing at attention to the very same Consulate official as had so recently advised me how to join the Air Transport Command.

He was now severely reprimanding me for doing anything so foolish. Didn't I realize I was alienating the great friendship which existed between our now-allied countries? Later, with a mischievous grin, he said I'd blown my opportunity by getting caught. But he became quite earnest when he said I mustn't try it again; this was a condition of the bargain he had struck to get me off the hook of my immigration misdemeanour. I had to phone him each day until he could find me transport back to Australia. This materialized about two weeks later in the form of dear old Queen Elizabeth and I became a semi-passenger back to Sydney under a Discharged Seamen's Agreement.

We carried thousands of American servicemen to Australia on what proved to be a pleasant voyage. Of all the remote outposts imaginable we stopped for refuelling at the French Marquesas Islands, northeast of Tahiti in the latitude of Peru. While there, I watched an amphibious aircraft, a U.S. Navy Kingfisher, trying to take off with an obvious overload of bombs. Each time the pilot made an abortive run he would drop one more bomb over the side. He finally got airborne but as he left the water his remaining bombload exploded and he disintegrated before my eyes. But the incident had a surprising and permanent effect on my life. That moment finally clinched my decision to make commercial flying my lifelong profession.

At San Francisco we learned that certain irregularities existed in the articles we had signed, and it became necessary for each crew member to sign off and, if he wished, to sign new articles. I accepted this as an opportunity to leave the ship legally, and put into train a scheme to sneak across the border into Canada and there offer myself to the British Air Transport Command.

The British Consul could offer little advice on joining this command from American soil, but did say many others had followed my proposed route and were now doing sterling service flying replacement aircraft to the British Isles. It was a great pity Bob Buckby, another old mate of mine did not follow this path. He joined a refrigeration ship in Sydney which was "bumped" in the Atlantic, with the result that both his legs had to be amputated due to frostbite. I recall going aboard with him while this ship was alongside the Pyrmont wharves in Sydney, and she had death written all over her. When I expressed these fears Bob showed not the slightest interest.

As I sneaked up to the Canadian border a giant American cop grabbed me, gave me a couple of vigorous shakes and marched me off to the local bastille. He mellowed when I explained my reasons for being at the border, but not sufficiently to close his eyes to his duty. Next morning found me standing at attention to the very same Consulate official as had so recently advised me how to join the Air Transport Command.

He was now severely reprimanding me for doing anything so foolish. Didn't I realize I was alienating the great friendship which existed between our now-allied countries? Later, with a mischievous grin, he said I'd blown my opportunity by getting caught. But he became quite earnest when he said I mustn't try it again; this was a condition of the bargain he had struck to get me off the hook of my immigration misdemeanour. I had to phone him each day until he could find me transport back to Australia. This materialized about two weeks later in the form of dear old Queen Elizabeth and I became a semi-passenger back to Sydney under a Discharged Seamen's Agreement.

We carried thousands of American servicemen to Australia on what proved to be a pleasant voyage. Of all the remote outposts imaginable we stopped for refuelling at the French Marquesas Islands, northeast of Tahiti in the latitude of Peru. While there, I watched an amphibious aircraft, a U.S. Navy Kingfisher, trying to take off with an obvious overload of bombs. Each time the pilot made an abortive run he would drop one more bomb over the side. He finally got airborne but as he left the water his remaining bombload exploded and he disintegrated before my eyes. But the incident had a surprising and permanent effect on my life. That moment finally clinched my decision to make commercial flying my lifelong profession.

Misfortune awaited my return home. I had missed my RAAF call-up and they had sacked me. When I went to see them they informed me in the most forthrigtrt manner that I had committed a crime by leaving the country after my acceptance for the Reserve. After ripping a strip off me for several minutes the officer in charge of the section became interested in my escapades and we spent some time in these reminiscences. Despite his obvious sympathy he could not intervene in my re-appointment. He told me my papers were marked that I was a 'bit of a lone wolf' and not amenable to discipline. He merely asked me to return my lapel badge.

Above: January1972 Western Harbour, Hong Kong. Ex-Queen Elizabeth (83,600 tons and 1031 feet in length) a burning hulk. Seawise University, Panama, Chapman College of Orange, California. Owners: Bland Navigation Company. Mr C.Y. Tong purchased for $HK3.2 million in 1970 at a Florida auction. Fire started Sunday 19 January 1972 at 10.30 a.m.