En Route

Things are always at their best in the beginning. Pascal

Into the dangerous world I leapt. Infant Sorrow. William Blake

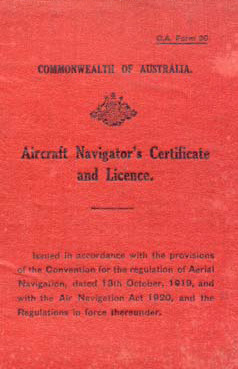

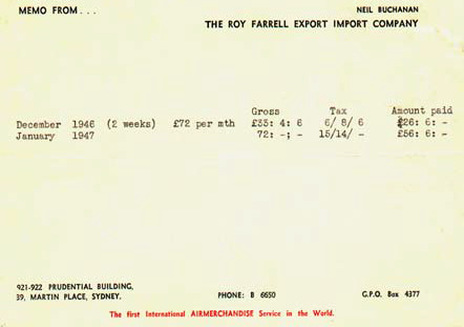

I walked into the Sydney office of The Roy Farrell Export-Import Company, 921- 922 Prudential Building, 39 Martin Place at 09:45 hours on Tuesday 17 December 1946. That day the sun smiled on me while good fortune quietly joined the queue. I expected to meet Manager Robert Bob Russell, but found my interviewer was an old acquaintance - Harry de Leuil. From the moment he hired me my life became an adventure punctuated by moments of terror. I was thrown into a kaleidoscope of new countries, strange smells and even stranger habits. The peoples’ skin and features were different yet their ambitions were not. All most people can hope for is a steady job to support their family and if one enjoys the work it is a bonus. My job was crammed with the latter! Regretfully, my appointment was to the chagrin of one Vernon Harold Dick Hunt who had waited with another applicant for the decision. Mr de Leuil’s choice was an imagined slur that Hunt never forgave and without having uttered a word or even meeting him I had made an enemy. Yet, I frankly concede this man was miles ahead of me in worldly experience and a pilot of class. Did my 2nd Class Navigator’s Licence, then a rarity, give me the edge or did this astute man see something in me that was not obvious? Perhaps, Mr de Leuil had made one of his few mistakes! Later when Dick Hunt joined the company his rise was meteoritic.

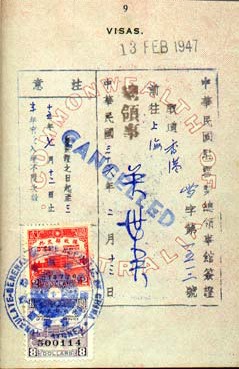

A pretty secretary helped me complete countless forms and checked my passport for visas. She nodded with approval when she found one for China as it was a thing of beauty that filled one page and was originally obtained to lead Eric McIllree’s flight of Ansons to the United Kingdom.

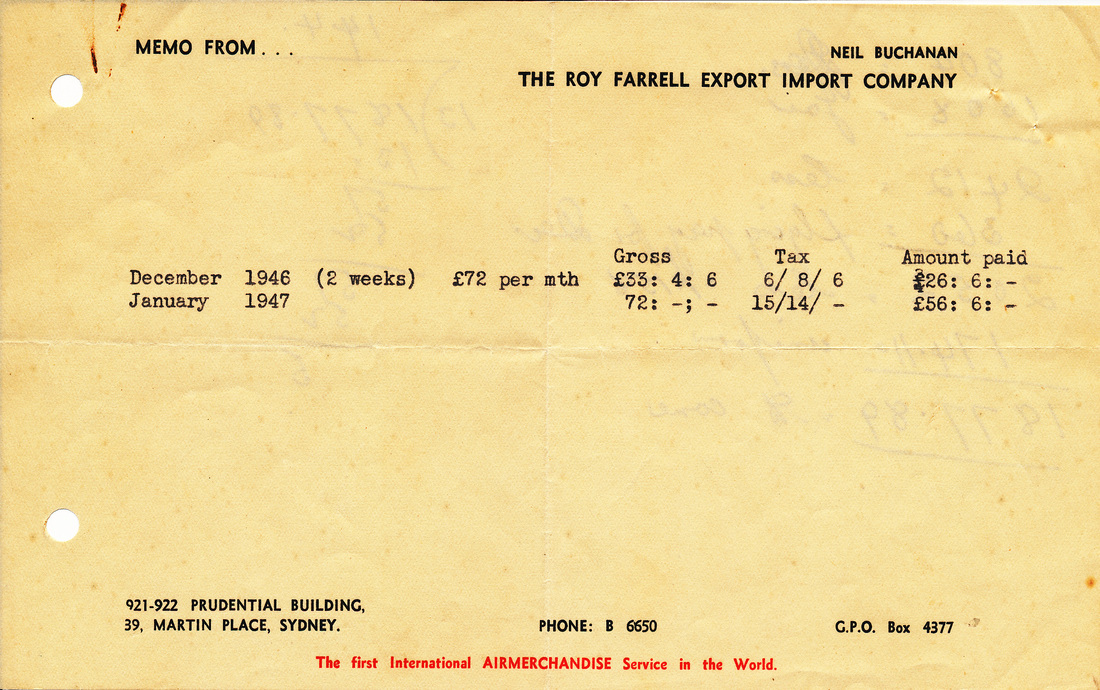

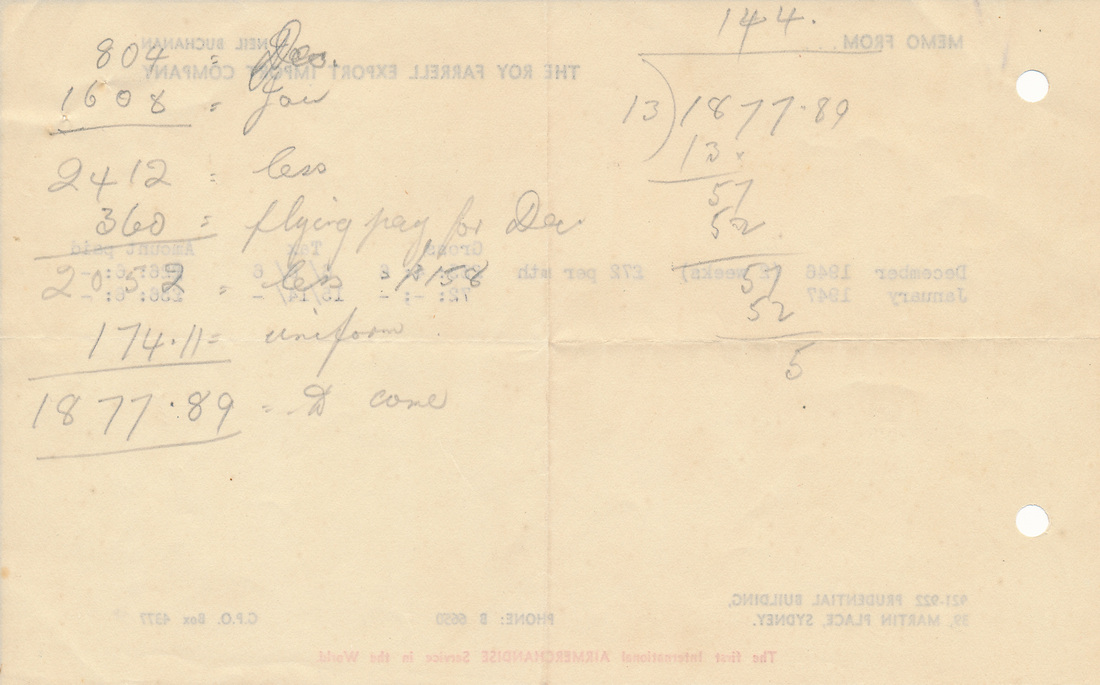

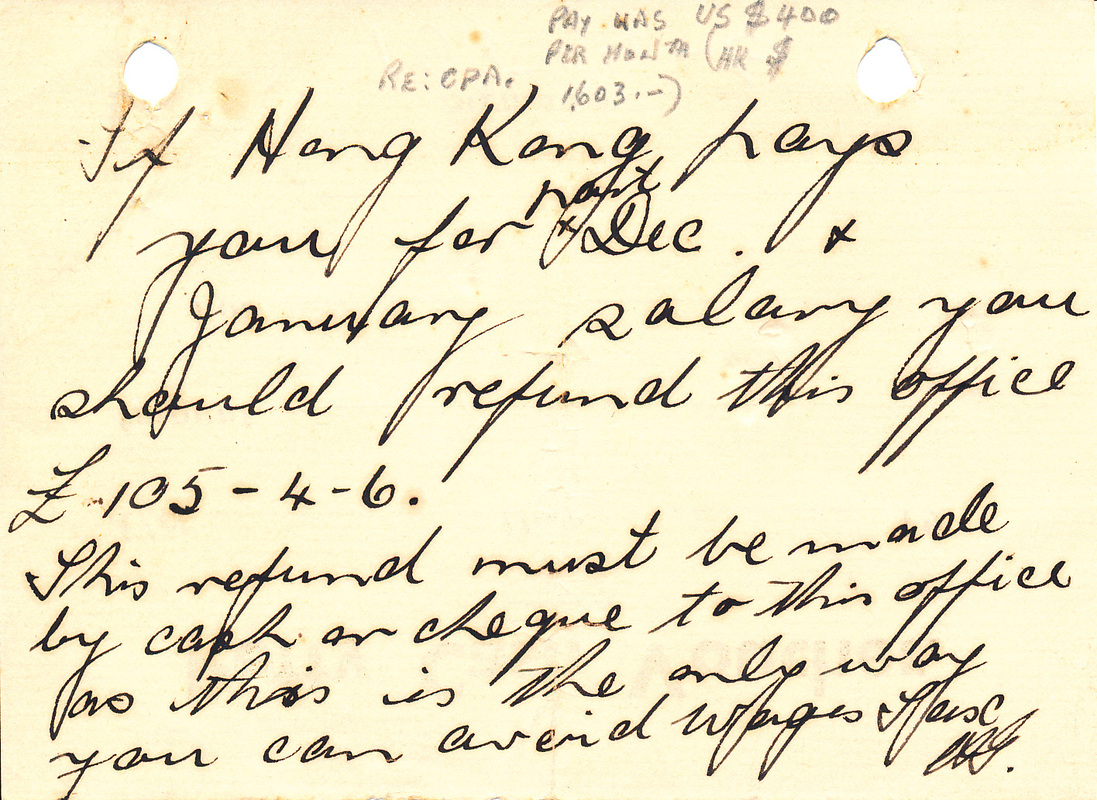

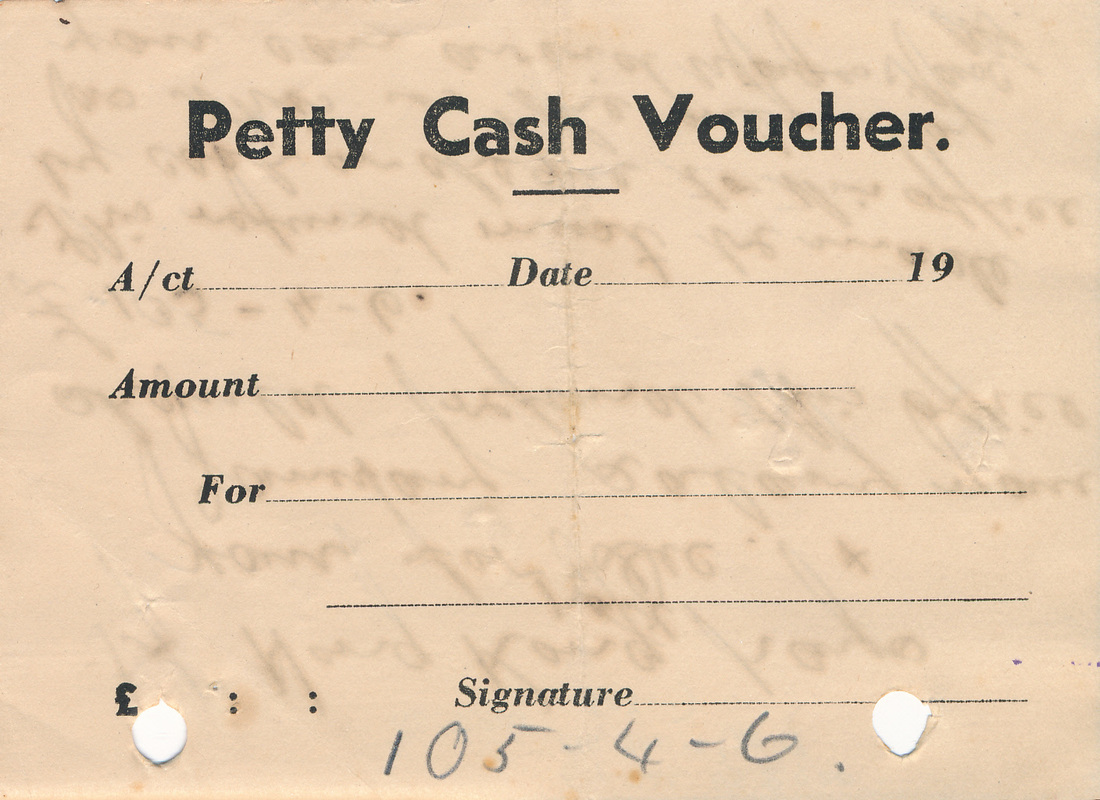

My monthly salary was $US 400, which on the free exchange rate, came to $HK 1,603. I felt like a merchant prince and found myself at peace with the world. Some of my tranquillity evaporated later in 1947 when first officers were hired in pounds sterling that equated to $HK 1,610!

(***Please see related images at the bottom of this page***)

A pretty secretary helped me complete countless forms and checked my passport for visas. She nodded with approval when she found one for China as it was a thing of beauty that filled one page and was originally obtained to lead Eric McIllree’s flight of Ansons to the United Kingdom.

My monthly salary was $US 400, which on the free exchange rate, came to $HK 1,603. I felt like a merchant prince and found myself at peace with the world. Some of my tranquillity evaporated later in 1947 when first officers were hired in pounds sterling that equated to $HK 1,610!

(***Please see related images at the bottom of this page***)

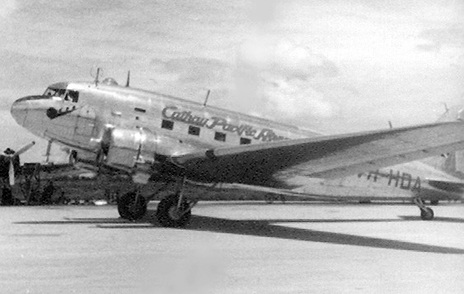

Forty hours later the glow of dawn painted a new day that found me at Sydney’s Mascot Airport strapped in the co-pilot’s seat of a Roy Farrell Export & Import Company DC3. With hardly a pause Capt. John Pinky Wawn poured on full power and I heard an audible groan as heavily laden VR-HDA left the ground. A wide gentle turn put us onto a heading for our first refuelling stop at Charleville and my thirty-two year Orient sojourn had begun.

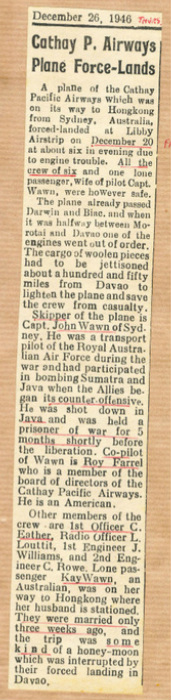

The flight progressed through Cloncurry, Darwin, Sorido - Biak and Pitoe - Morotai without a problem, but excitement and danger lay ahead. We carried a cargo of mainly woollen goods in 180- pound bales. Meanwhile, I got to know the others aboard. Capt. Roy Farrell shared the co-pilot duties with me and Lyall Mum Louttit was our sparks. The others aboard were ground engineers Bill Hokum Harris, Jack Williams and Charlie Rowe. Hokum was Cathay’s chief engineer, Jack Williams became prominent in the Hong Kong Aircraft Engineering Company (HAEC) and Charlie Rowe was an instrument man of rare ability. This was a notable trio of engineering talent, however Pinky’s bride Kay made the cabin glow with no qualifications other than her beauty.

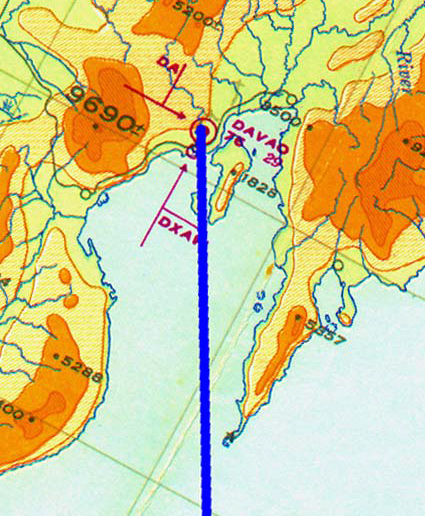

We landed at Morotai’s tiny Pitoe strip in heavy rain that strengthened Morotai’s reputation for foul weather. Morotai is an island just beyond the Equator at the northern tip of the Celebes. To my mind, the Celebes resembles a dancing elephant with its trunk in reverse. For a man who is a strict teetotaller this shows I possess the unique imagination generally reserved for one in advanced DTs. We refuelled and took off in driving rain. The thin scorching air added to the length of our take-off and with coco palms flashing perilously close I questioned my chosen career. Finally, when fate decided it had sufficient amusement Pinky got us into the air, but this was only was a brief respite as continuous turbulence and lightning strikes prevented us from suffering boredom. Just when a betting man would wager things could not get worse the port engine packed up. At this stage we were an hour out of Morotai cruising at 9,000 feet and with George doing his best to relieve our workload I had a spare moment to think I probably was in the wrong environment.

The flight progressed through Cloncurry, Darwin, Sorido - Biak and Pitoe - Morotai without a problem, but excitement and danger lay ahead. We carried a cargo of mainly woollen goods in 180- pound bales. Meanwhile, I got to know the others aboard. Capt. Roy Farrell shared the co-pilot duties with me and Lyall Mum Louttit was our sparks. The others aboard were ground engineers Bill Hokum Harris, Jack Williams and Charlie Rowe. Hokum was Cathay’s chief engineer, Jack Williams became prominent in the Hong Kong Aircraft Engineering Company (HAEC) and Charlie Rowe was an instrument man of rare ability. This was a notable trio of engineering talent, however Pinky’s bride Kay made the cabin glow with no qualifications other than her beauty.

We landed at Morotai’s tiny Pitoe strip in heavy rain that strengthened Morotai’s reputation for foul weather. Morotai is an island just beyond the Equator at the northern tip of the Celebes. To my mind, the Celebes resembles a dancing elephant with its trunk in reverse. For a man who is a strict teetotaller this shows I possess the unique imagination generally reserved for one in advanced DTs. We refuelled and took off in driving rain. The thin scorching air added to the length of our take-off and with coco palms flashing perilously close I questioned my chosen career. Finally, when fate decided it had sufficient amusement Pinky got us into the air, but this was only was a brief respite as continuous turbulence and lightning strikes prevented us from suffering boredom. Just when a betting man would wager things could not get worse the port engine packed up. At this stage we were an hour out of Morotai cruising at 9,000 feet and with George doing his best to relieve our workload I had a spare moment to think I probably was in the wrong environment.

At that very moment Roy Farrell exclaimed that Pinky had feathered the prop and the height had stabilised. As I scrambled back to the flight deck Jack and Charlie latched the door. I could hardly believe my eyes the altimeter read 1,500 feet. As a new boy and reluctant to make more of a fool of myself than absolutely necessary I stared but held my tongue. The loss of 7,500 feet is a sobering thought and of greater interest – what if there had been no 7,500 feet to lose? That lesson stayed with me all my flying life and I never rushed my pre-flight checks.

Reaction to my close miss with disaster did not set in until some two days later. Then my overactive imagination saw visions of natives dodging bales of woollen goods, of no earthly use to them, interspersed by an uninvited portly body arriving through a thatched roof and demanding nosh.

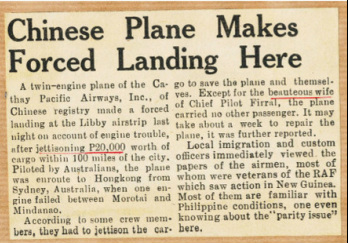

On a realistic level RFE&IC had lost 20,000 pesos of cargo jettisoned 150 miles from Davao and sundry items of expensive aircraft equipment. It came as no surprise when an extensive search by the authorities recovered nothing. The reprieve of our plane was due to Pinky’s recollection that the erring prop was changed in Sydney in a rush. He correctly figured it was not bled correctly. As the airstream turned the prop he pushed the pitch lever that changed the blade angle and pressed the feather button. This proved successful.

As the used fuel decreased the planes weight Pinky showed his class by coaxing his lame duck to 3000 feet.

Reaction to my close miss with disaster did not set in until some two days later. Then my overactive imagination saw visions of natives dodging bales of woollen goods, of no earthly use to them, interspersed by an uninvited portly body arriving through a thatched roof and demanding nosh.

On a realistic level RFE&IC had lost 20,000 pesos of cargo jettisoned 150 miles from Davao and sundry items of expensive aircraft equipment. It came as no surprise when an extensive search by the authorities recovered nothing. The reprieve of our plane was due to Pinky’s recollection that the erring prop was changed in Sydney in a rush. He correctly figured it was not bled correctly. As the airstream turned the prop he pushed the pitch lever that changed the blade angle and pressed the feather button. This proved successful.

As the used fuel decreased the planes weight Pinky showed his class by coaxing his lame duck to 3000 feet.

We landed at the old Japanese Libby Airstrip at Davao in southern Mindanao. Roy Farrell found us rooms at Guino’s Hotel where I made the acquaintance of the biggest mosquitoes in my experience. Jack Williams tells a story of his encounter with them. He awoke to the sound of squabbling voices and as his eyes adjusted to the half-light he saw two massive mosquitoes perched on the end of his bed. One mossie said to the other, Should we eat him here or take him to the river? His worldlier mate was adamant that dis was the place for if they took him to the river the big bastard would steal him from them! Throughout the night cables flashed to and from Manila. Roy Farrell learned there was a spare engine at Manila and as luck would have it Betsy had a lay over there. At first light she brought the spare engine and immediately returned to Manila with Pinky and me aboard. Pinky waited in Manila as relief commander for a seaman charter that originated in Shanghai and currently en-route to New Zealand.

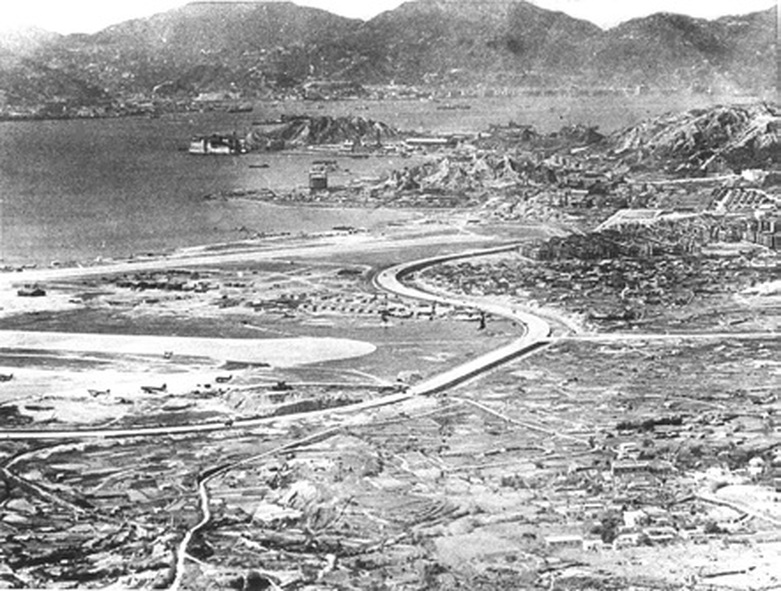

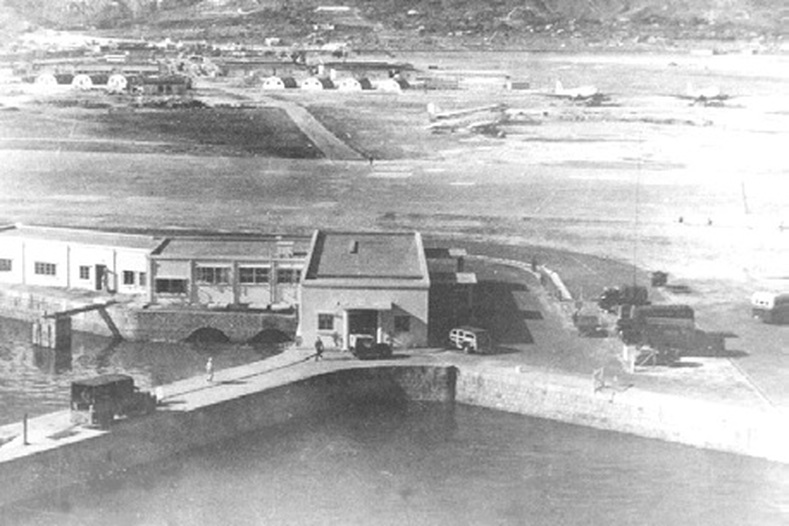

Late in the afternoon of 21 December 1946 I arrived in Hong Kong. With the pace that things were happening this virile company would burn me out within a month. But how wrong were those thoughts for I thrived on what lay ahead. For the next three decades Kai Tak was to be my home from home as I trudged through its sludgy mud or powdery dust. That afternoon it was mud as our touchdown had followed the end of a rainsquall that left Runway 13 a shallow lake of water.

Late in the afternoon of 21 December 1946 I arrived in Hong Kong. With the pace that things were happening this virile company would burn me out within a month. But how wrong were those thoughts for I thrived on what lay ahead. For the next three decades Kai Tak was to be my home from home as I trudged through its sludgy mud or powdery dust. That afternoon it was mud as our touchdown had followed the end of a rainsquall that left Runway 13 a shallow lake of water.

I tiptoed along a precarious system of duckboards that led to a gaggle of Army tents erected along the southern seawall. These palatial facilities housed Immigration, Customs and Health. My spirit was at its lowest ebb! Yet, an effort to improve this Spartan reception was under construction some three hundred yards to the west and adjacent to the flying boat slipway. This became the first postwar terminal building.

I recall meeting a hefty policeman named Superintendent F. Buck Indge- Buckingham. It was thirty years before I learned his full name and only then by chance. I attended the reception of a cricket pal Buddy Carnel who married Buck’s daughter Peta and the invitation card revealed it.

But, to return to the tent city. Near the exit flap stood a smiling Syd de Kantzow who warmly shook my hand. The smile later proved uncharacteristic for it was rarely displayed. In a spirit of friendship he introduced me to Cathay’s public relations man Bill Dobson. Then with a nod from Buck we walked to the centre of the field.

I recall meeting a hefty policeman named Superintendent F. Buck Indge- Buckingham. It was thirty years before I learned his full name and only then by chance. I attended the reception of a cricket pal Buddy Carnel who married Buck’s daughter Peta and the invitation card revealed it.

But, to return to the tent city. Near the exit flap stood a smiling Syd de Kantzow who warmly shook my hand. The smile later proved uncharacteristic for it was rarely displayed. In a spirit of friendship he introduced me to Cathay’s public relations man Bill Dobson. Then with a nod from Buck we walked to the centre of the field.

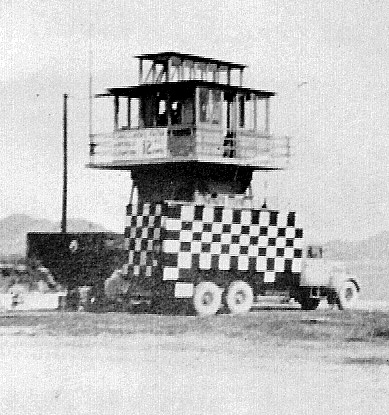

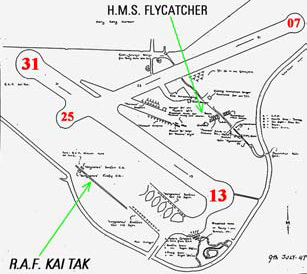

From that vantage point Syd gave me a concise familiarisation briefing. His finger traced the RAF Control Tower that controlled all plane movements, then moved to the HMS Flycatcher and the RAF establishments. He pointed out the hills that rise alarmingly to embrace the field to the east and north. Though the ground to the west was somewhat lower it also presented pilot hazards. Fixing me with a beady eye Syd snarled I never must be party to a take-off on Runway 31 that pointed towards to Lion Rock. To drive home his point he described in gory detail the crash of a RAF Dakota three months earlier on 25 September. Nineteen lives were lost when it crashed into the foothills of Kowloon Tong after a 31 take-off. To my relief he moved south to the Japanese War Memorial that gleamed in the afternoon sun atop Mount Cameron. The Japanese built it to dominate the four corners of the Colony and as a bonus found it reflected the sun’s rays from about eleven o’clock onwards. Except on the cloudiest days its reflection was visible from Pratas Reef some 90 miles in the China Sea. The Japs were long gone however it proved a valuable navigation aid for us pilots. With a few other minor remarks Syd brought the briefing to a close and told me to hop aboard a car he drove. Bill Dobson had doubtless experienced his driving and found more pressing things to do. This drive became the most dangerous part of all for Syd weaved in and out of traffic with proprietorial disdain. Other road users seemed conversant with his methods and moved swiftly to the safe haven of the curb. I was terrified but my fixed grin seemed to give him the impression I enjoyed his bout with Providence and he seemed to mellow towards me. He must have covered the five miles in as many minutes and with screeching brakes and burnt rubber deposited me at the main doors of the imposing Peninsula Hotel. The Company then reserved two rooms for transiting crew in what we referred to as the upholstered sewer. Each room was crammed with camp beds that never seemed empty. The one Syd selected for me proved full of sleep yet such luxury lasted just two nights.

Meanwhile, I spent every minute completing company forms, running around after visas, licence conversions and a rat race of smaller chores. It came as a relief on 23 December when I found myself on VR-HDG on the way back to Sydney. On 30 December I was back in the Peninsula Hotel snug as a bug in a rug in my favourite camp bed. My logbook shows that first fortnight with Cathay Pacific logged me 94 hours flying. This was an impressive one and a half return flights to Sydney. The longest day’s work was a flying time of 18 hours 25 minutes. During that fortnight I had two days off. How was I overlooked for such a generous time – obviously there was no available plane.

Meanwhile, I spent every minute completing company forms, running around after visas, licence conversions and a rat race of smaller chores. It came as a relief on 23 December when I found myself on VR-HDG on the way back to Sydney. On 30 December I was back in the Peninsula Hotel snug as a bug in a rug in my favourite camp bed. My logbook shows that first fortnight with Cathay Pacific logged me 94 hours flying. This was an impressive one and a half return flights to Sydney. The longest day’s work was a flying time of 18 hours 25 minutes. During that fortnight I had two days off. How was I overlooked for such a generous time – obviously there was no available plane.