Dr Lancelot Rutherford

Late in 1950 General Ne Win decided that his army had cleared the insurgents far enough from the 'three R's' (road, rail and river) to make them useable. Surface transport could do the job that had been performed by costly airfreight. Air Burma's proprietor, Bo Setkya, began winding up the show and asked Harry de Leuil to find a sale for his aircraft. Harry explained that this type of aircraft was becoming obsolete, that it could take a considerable time to find suitable buyers, and that those buyers would expect to name their own price.

'These statements made him quite unhappy,' Harry recalled recently, 'so I made him an alternative suggestion that he might like to approach the War Office with a blanket offer of all the aircraft and spares for a price he considered satisfactory.

'I reminded him that success or failure depended on convincing the General that it would boost his prestige as Supreme Commander of the Burmese Defence Forces if he could add a ready-made transport wing to his Air Force. This proved a relatively simply task, and as Ne Win was the real power behind the throne the Government readily acceded to the "suggestion". There followed a period of intense inspection and testing by the Burmese Air Force, and then in December Air Burma's equipment passed to Air Force control!'

'These statements made him quite unhappy,' Harry recalled recently, 'so I made him an alternative suggestion that he might like to approach the War Office with a blanket offer of all the aircraft and spares for a price he considered satisfactory.

'I reminded him that success or failure depended on convincing the General that it would boost his prestige as Supreme Commander of the Burmese Defence Forces if he could add a ready-made transport wing to his Air Force. This proved a relatively simply task, and as Ne Win was the real power behind the throne the Government readily acceded to the "suggestion". There followed a period of intense inspection and testing by the Burmese Air Force, and then in December Air Burma's equipment passed to Air Force control!'

Despite

my love of the country and its people I resigned from the Union of Burma

Airways towards the end of 1951, a move that had been necessitated

by my wife's slow

convalescence in Burma's unsuitable climate. Joyce's illness had been serious

and for months she lay at death's door. There were no health benefits for the

individual in Burma and all our savings were dissipated. On November 2 we

caught a BOAC Argonaut out of Mingaladon, bound for Sydney.

Eric Mcillree came to my aid the very next day, offering me a job with his Amphibious Airways, a New Guinea company which operated two Avro-Ansons and two Walrus amphibians. When I arrived in the country I found all personnel giving of their best, but there was a tendency to cut Civil Aviation corners.

Early one morning both Ansons departed Rabaul for Wewak, with technical landings planned for Hoskins, on the southeast coast of New Britain, and Madang. I was commanding one Anson with a full load of ten natives and a white plantation manager who occupied the right-hand pilot seat. The other aircraft, on paper, was under the command of a Dutchman named Jan Patcha, with Eric accompanying him ostensibly as a passenger but really in charge because of Jan's inexperience with the type. This was the first corner we were cutting, as Eric had no Commercial Licence. The next pruning was that we had stated that our intention was to land at Hoskins to pick up fuel from our private cache located there at high cost. We had decided we would not actually land there, and had prepared a series of erroneous position reports. To achieve this economy we left Rabaul overloaded with full fuel tanks.

As the flight progressed these things preyed on my conscience and I suddenly felt quite ill. I radioed Eric that I wasn't feeling well and intended landing at Hoskins. This we did, and after discussion decided that Jan would act as my co-pilot and Eric would take the other Anson on by himself. He realised he didn't have the required qualification but figured there was little chance he would be caught.

For some unaccountable reason two departmental officers were awaiting our arrival at Wewak, the upshot being that our licences were suspended: Eric's for flying for 'hire or reward' without licencing authority, and mine due to illness. My licence was subsequently revalidated after an interview with a well-known Sydney psychiatrist. Eric's was returned to him after a severe reprimand.

Eric died in September 1973, chief of the massive Avis Rent-a-Car empire. He was ever a good friend, and I appreciated the two short periods I worked for him.

Back in Sydney Joyce was still in a convalescent home, expenses were mounting at a greater rate than my earnings, so in March 1952 I returned to the Union of Burma Airways where I threw myself into my job with increased vigor. Union of Burma rosters for the next couple of years showed a fairly stabilised pilot contingent mainly of Englishmen. Of these, Captain Alex Hare had the most interesting experience. On June 26, 1954 the DC3 he was commanding was skyjacked by a trio of bomb and pistol-packing dissidents who forced him to land on a beach on the Arakanese coast and there joyously relieved him of his custodial worries by removing 200,000 pounds sterling in currency. Their elevation to affluence was short-lived; for they themselves were almost immediately nobbled and murdered by another equally joyous band of brigands. Click here to see more.

Eric Mcillree came to my aid the very next day, offering me a job with his Amphibious Airways, a New Guinea company which operated two Avro-Ansons and two Walrus amphibians. When I arrived in the country I found all personnel giving of their best, but there was a tendency to cut Civil Aviation corners.

Early one morning both Ansons departed Rabaul for Wewak, with technical landings planned for Hoskins, on the southeast coast of New Britain, and Madang. I was commanding one Anson with a full load of ten natives and a white plantation manager who occupied the right-hand pilot seat. The other aircraft, on paper, was under the command of a Dutchman named Jan Patcha, with Eric accompanying him ostensibly as a passenger but really in charge because of Jan's inexperience with the type. This was the first corner we were cutting, as Eric had no Commercial Licence. The next pruning was that we had stated that our intention was to land at Hoskins to pick up fuel from our private cache located there at high cost. We had decided we would not actually land there, and had prepared a series of erroneous position reports. To achieve this economy we left Rabaul overloaded with full fuel tanks.

As the flight progressed these things preyed on my conscience and I suddenly felt quite ill. I radioed Eric that I wasn't feeling well and intended landing at Hoskins. This we did, and after discussion decided that Jan would act as my co-pilot and Eric would take the other Anson on by himself. He realised he didn't have the required qualification but figured there was little chance he would be caught.

For some unaccountable reason two departmental officers were awaiting our arrival at Wewak, the upshot being that our licences were suspended: Eric's for flying for 'hire or reward' without licencing authority, and mine due to illness. My licence was subsequently revalidated after an interview with a well-known Sydney psychiatrist. Eric's was returned to him after a severe reprimand.

Eric died in September 1973, chief of the massive Avis Rent-a-Car empire. He was ever a good friend, and I appreciated the two short periods I worked for him.

Back in Sydney Joyce was still in a convalescent home, expenses were mounting at a greater rate than my earnings, so in March 1952 I returned to the Union of Burma Airways where I threw myself into my job with increased vigor. Union of Burma rosters for the next couple of years showed a fairly stabilised pilot contingent mainly of Englishmen. Of these, Captain Alex Hare had the most interesting experience. On June 26, 1954 the DC3 he was commanding was skyjacked by a trio of bomb and pistol-packing dissidents who forced him to land on a beach on the Arakanese coast and there joyously relieved him of his custodial worries by removing 200,000 pounds sterling in currency. Their elevation to affluence was short-lived; for they themselves were almost immediately nobbled and murdered by another equally joyous band of brigands. Click here to see more.

|

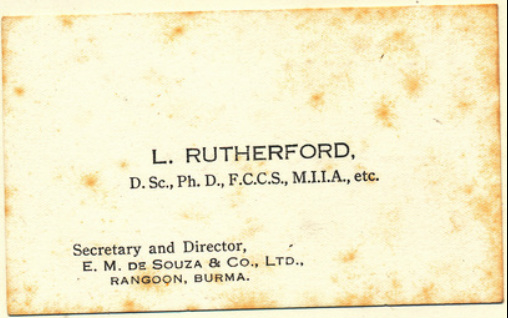

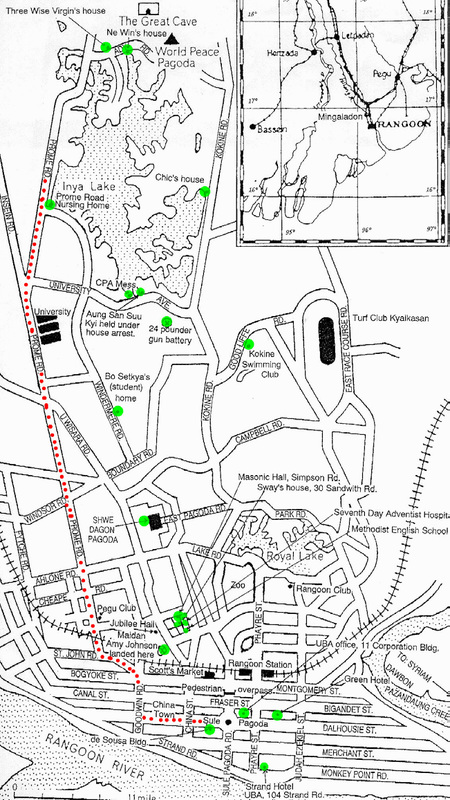

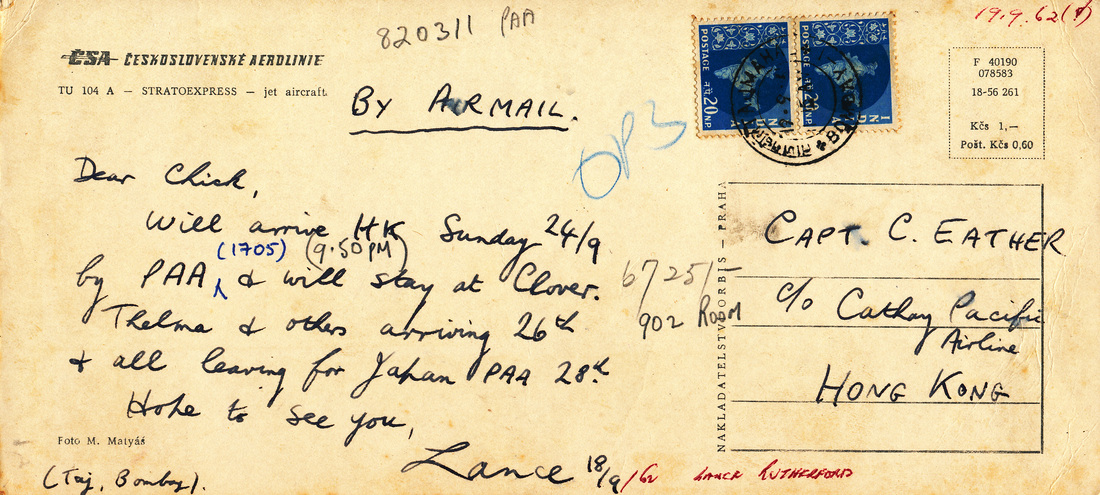

On my earlier tour I had become acquainted with Lance Rutherford when I was initiated into the Brotherhood of Free Masons in the Lodge Pegu, which operated under the English constitution in Burma and was numbered 3330. The date of my initiation was July 25, 1951. Lance was the general manager and major shareholder of the giant pharmacy empire of E.M. de Souza and Company Limited.

|

He was a terribly reserved character and quite incapable of easy friendship, but for some unaccountable reason he and I clicked almost from our first handshake, and became close friends. He shared with me my interest in the occult, and during one of our early chats he calmly made a statement I have reason never to forget. Of that, more later. Like myself he adored Burma. 'He spent every leave he could arrange trekking through the most inaccessible terrain of its northern reaches.

On one such jaunt he teamed up with Frank and Jean Kingdon-Ward.

Kingdon-Ward has written two books about the wilder reaches of Upper Burma, Return to the Irrawaddy and Burma's Icy Mountains. In the former he mentions Lance frequently throughout the first fifty pages, most of these references being disparaging - a great pity, for Lance held this man in the highest regard. On New Year's Day in 1953 Jean Kingdon-Ward and Lance boarded my DC3, XY-ACO of the UBA fleet at Myitkyina, and I flew them to Putao, which the British call Port Hertz. It snuggles in the most northerly reaches of Burma, peopled by a conglomeration of hill-dwellers, loosely termed Kachins. The operations department of UBA had given me strict instructions that I must not attempt the flight unless I could make it completely in the clear, and that I must abandon it if when I reached the hamlet of Sumprabum I could not see Putao. But that day the visibility throughout the brief 45-minute flight was more than a hundred miles, and we were treated to an astonishing panorama of 'Burma's Icy Mountains' with The Triangle so vividly clear I felt I could see a mosquito winking his eye.

On one such jaunt he teamed up with Frank and Jean Kingdon-Ward.

Kingdon-Ward has written two books about the wilder reaches of Upper Burma, Return to the Irrawaddy and Burma's Icy Mountains. In the former he mentions Lance frequently throughout the first fifty pages, most of these references being disparaging - a great pity, for Lance held this man in the highest regard. On New Year's Day in 1953 Jean Kingdon-Ward and Lance boarded my DC3, XY-ACO of the UBA fleet at Myitkyina, and I flew them to Putao, which the British call Port Hertz. It snuggles in the most northerly reaches of Burma, peopled by a conglomeration of hill-dwellers, loosely termed Kachins. The operations department of UBA had given me strict instructions that I must not attempt the flight unless I could make it completely in the clear, and that I must abandon it if when I reached the hamlet of Sumprabum I could not see Putao. But that day the visibility throughout the brief 45-minute flight was more than a hundred miles, and we were treated to an astonishing panorama of 'Burma's Icy Mountains' with The Triangle so vividly clear I felt I could see a mosquito winking his eye.

The Burma political situation now began to disturb me. Although the country had a civilian democratic form of government the rumblings from General Ne Win's armed services, which he controlled with almost complete autocracy, became more audible. I discussed my fears with several colleagues, but was assured that in this land of waving palms, golden pagodas and happy folk, nothing of the sort could happen. I felt that so many well-informed and astute people could not be wrong and for a short while I put my fears behind me, but significant event followed significant event, and when Captain Pat Moore, then Operations Manager for Cathay Pacific, offered me a first officer position I grasped the opportunity with both hands and feet. In June 1953 I returned to the fold and there I stayed.

Though it took longer than I thought my native cunning proved more value to me than my well-informed advisors. On the morning of March 2, 1962 a young Karen nurse, hearing a rumble that rose in intensity, left the cool interior of the Prome Road Nursing Home at the 5 1/2 mile mark on Kokine Lakes and joined her Matron, Sister Heather Ba Than. Together they watched as tank after tank roared past on their way to Rangoon to take over the country in a coup d'etat.

The palms continued to wave, the pagodas glowed golden, but the people smiled no more.

U Sway Tin, UBA's general manager, forwarded me a newspaper cutting which reported Lance Rutherford's death. He also wrote: 'It was a good thing in a way that Dr Rutherford did not live to see all that he had built up taken away in the mass nationalisation of business houses throughout the country.

'On the morning of March 19, 1964 there was unusual activity among the army personnel, but at that time there seemed little significance. A few minutes past noon the army convoys moved into the city and began dropping off small groups of uniformed men at each street corner. These men then paired off and marched into the surrounding shops and stores. A short time later officers arrived in well-kept army transports and called at each of the commercial houses, one after another. On being presented to the owner or manager the officer would announce that the firm or company had been nationalised.

The palms continued to wave, the pagodas glowed golden, but the people smiled no more.

U Sway Tin, UBA's general manager, forwarded me a newspaper cutting which reported Lance Rutherford's death. He also wrote: 'It was a good thing in a way that Dr Rutherford did not live to see all that he had built up taken away in the mass nationalisation of business houses throughout the country.

'On the morning of March 19, 1964 there was unusual activity among the army personnel, but at that time there seemed little significance. A few minutes past noon the army convoys moved into the city and began dropping off small groups of uniformed men at each street corner. These men then paired off and marched into the surrounding shops and stores. A short time later officers arrived in well-kept army transports and called at each of the commercial houses, one after another. On being presented to the owner or manager the officer would announce that the firm or company had been nationalised.

'Dr Rutherford's company of De Souza was one of the first places visited.

A couple of minutes after the officer had made his proclamation a truck rolled up and the soldiers from it erected a large green-coloured signboard bearing the words in Burmese: 'People's Shop Number 9999'. All the other shops and businesses were also placarded as being the property of the State, but each had a smaller number than the De Souza establishment.'

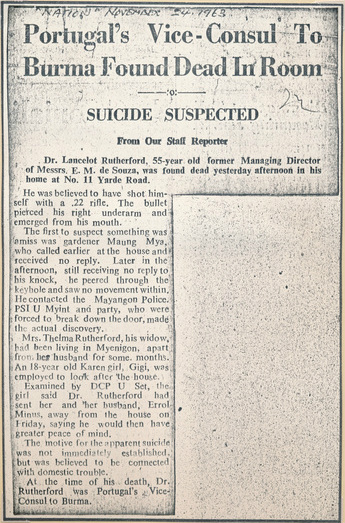

The terrifying statement that Lance had confided to me was that he knew the exact date he would die and how it would happen. He added, 'Although my death will be accepted as suicide, I will in fact be killed'. True to his forecast the Nation newspaper reported November 23, 1963 as the day he died 'a suspected suicide ... The .22 bullet which ended his life pierced his right underarm and emerged from his mouth.' Suicide?

A couple of minutes after the officer had made his proclamation a truck rolled up and the soldiers from it erected a large green-coloured signboard bearing the words in Burmese: 'People's Shop Number 9999'. All the other shops and businesses were also placarded as being the property of the State, but each had a smaller number than the De Souza establishment.'

The terrifying statement that Lance had confided to me was that he knew the exact date he would die and how it would happen. He added, 'Although my death will be accepted as suicide, I will in fact be killed'. True to his forecast the Nation newspaper reported November 23, 1963 as the day he died 'a suspected suicide ... The .22 bullet which ended his life pierced his right underarm and emerged from his mouth.' Suicide?

Lancelot and his wife, Hisako were married in Tokyo, Japan in early 1956. Hisako expired from heart failure brought on through rheumatic fever on 7 September 1958.

Lancelot died from suspected suicide on 23 November 1963.

Lancelot died from suspected suicide on 23 November 1963.