Shades of '007'

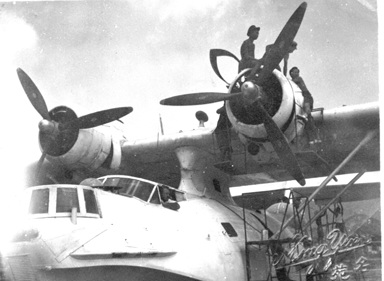

The Nationalist capital now changed from Chungking to Cheng-tu, yet Cathay Pacific continued to accept charters. Unfortunately its DC4 was fully engaged on airline schedules and Cathay farmed out these charters to MATCO whose Catalinas were ideal for a seventeen hour flight with fuel to spare. These were flights where anything could happen and frequently did!

Ian Fleming, famous for the 007 novels asked Captain Len Cos Cosgrove to record some of these flights, and in a moment of weakness Cos did so. He sent them to Fleming who would add the sex interest to these authentic adventures. Unfortunately, Fleming had the temerity to die and Cos’s great yarns seemed to die with the legendary writer. Cos sent them to me, and they are too good to fall into oblivion - here they are.

Ian Fleming, famous for the 007 novels asked Captain Len Cos Cosgrove to record some of these flights, and in a moment of weakness Cos did so. He sent them to Fleming who would add the sex interest to these authentic adventures. Unfortunately, Fleming had the temerity to die and Cos’s great yarns seemed to die with the legendary writer. Cos sent them to me, and they are too good to fall into oblivion - here they are.

The Two Airfields of Cheng-tu

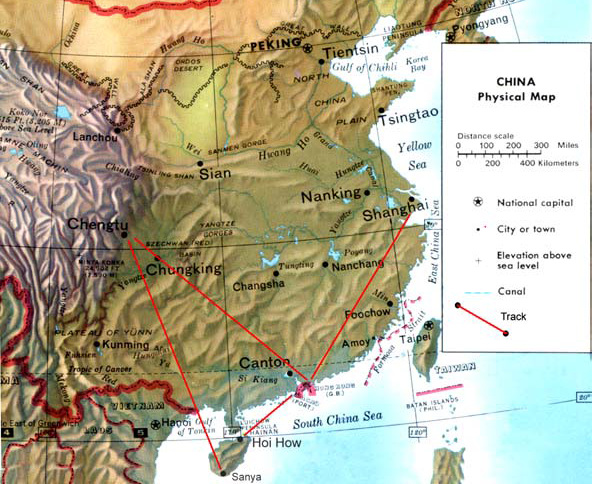

At this time, throughout the Far East, only two aircraft had the range to fly to Cheng-tu then return without refuelling. They were the Skymaster and the Catalina, and the nearest Skymaster was engaged elsewhere. So the Catalina was selected and MATCO’s operations manager leapt to accept the assignment from Cathay Pacific. The choice of pilot fell on Bohm, as Cosgrove flatly refused to touch the operation. The co-pilot was Jim Kiernan, as there was no one else. A Chinese radioman that knew the area and spoke its dialect was hastily found. With tanks filled to overflowing VR-HDS, with a special dispensation, carried out a night take-off from Kai Tak and set out on her incredible journey.

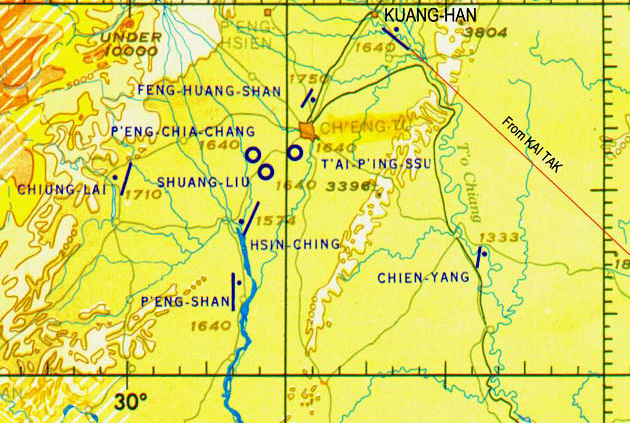

Cheng-tu lies almost 1000 miles north-west of Hong Kong on a high plateau marking the last great spur of the Himalayan thrust into China. The airfields were Cheng-tu‘s T`ai-P`ing Ssu and Kuang-han. The first a small but adequate field on the plateau to the south south west of the city, the other a wartime monstrosity built for the fighting B17s on the bottom of a sheer-sided valley. Kuang-han was Bohm’s destination. He had been advised that a radio beacon of limited power was still operational, and the passengers he was to pick up would be ready for a quick turn around.

Bohm planned to keep the very high ground well to port and to rendezvous with the beacon at the maximum height he could attain. His Chinese radio operator indicated a safe letdown over the plateau, which consisted of one-minute legs to north and south of the beacon. Then, all being well, a safe descent to 500 feet above the plateau’s highest point of 3,804 feet would be a piece of cake. His early departure should bring him over the city of Cheng-tu just after dawn with plenty of daylight.

But as daylight grew the wisps of clouds below him thickened into a solid sheet, and uneasily aware of the rising ground below it, Bohm was forced to claw for yet more altitude. The outside air temperature fell rapidly as height increased and would fall even further as his flight took him north-west. He hoped that the

front he was penetrating would prove narrow and that he would soon come out of it into the cold clear air of the monsoon blowing out of Siberia. He watched the thin ribbon of white forming at the bottom of the windscreen and hunched deeper into his flying jacket. Kiernan shifted uneasily and jabbed an expressive thumb towards the spreading white area on the side windows. However, VR-HDS would not be coaxed any higher - she was not fitted with any form of de-icing equipment. Then Bohm remembered that ice was the salient factor that had led Cosgrove to refuse the flight.

Cheng-tu lies almost 1000 miles north-west of Hong Kong on a high plateau marking the last great spur of the Himalayan thrust into China. The airfields were Cheng-tu‘s T`ai-P`ing Ssu and Kuang-han. The first a small but adequate field on the plateau to the south south west of the city, the other a wartime monstrosity built for the fighting B17s on the bottom of a sheer-sided valley. Kuang-han was Bohm’s destination. He had been advised that a radio beacon of limited power was still operational, and the passengers he was to pick up would be ready for a quick turn around.

Bohm planned to keep the very high ground well to port and to rendezvous with the beacon at the maximum height he could attain. His Chinese radio operator indicated a safe letdown over the plateau, which consisted of one-minute legs to north and south of the beacon. Then, all being well, a safe descent to 500 feet above the plateau’s highest point of 3,804 feet would be a piece of cake. His early departure should bring him over the city of Cheng-tu just after dawn with plenty of daylight.

But as daylight grew the wisps of clouds below him thickened into a solid sheet, and uneasily aware of the rising ground below it, Bohm was forced to claw for yet more altitude. The outside air temperature fell rapidly as height increased and would fall even further as his flight took him north-west. He hoped that the

front he was penetrating would prove narrow and that he would soon come out of it into the cold clear air of the monsoon blowing out of Siberia. He watched the thin ribbon of white forming at the bottom of the windscreen and hunched deeper into his flying jacket. Kiernan shifted uneasily and jabbed an expressive thumb towards the spreading white area on the side windows. However, VR-HDS would not be coaxed any higher - she was not fitted with any form of de-icing equipment. Then Bohm remembered that ice was the salient factor that had led Cosgrove to refuse the flight.

Kiernan made another expressive gesture, and this time his thumb indicated the direction of his thinking. Back to Honkers. Bohm shook his head, arguing that they were only an hour or two out and the beacon should come in loud and clear any time now. He promised he would return home if there were no improvement in weather conditions in an hour or so. Kiernan resumed his sombre contemplation of the zero visibility and found he longed for a paper-run back in his beloved Perth.

Some forty minutes later the wandering needle of the radio compass seized on a signal and wavered round a point some ten degrees to port. Swiftly Bohm tuned in the stand-by compass and that too spun leisurely to the same heading. The radio operator confirmed the Morse lettering from his notebook and the tension on the flight deck lessened. Bohm considered the situation. His Catalina was staggering at 12,000 feet, the bearing of the station now showed he was on the safe side of the plateau. He gently wound the nose down and then disengaging the autopilot he set himself the task of orientating his arrival over the beacon. Repeated calls by his radio operator produced no response. Their only connection with an outer world was the KC, KC, KC of the homing beacon. That, at least, proved that some devoted soul in the wilderness below was doing his best to assist the airborne foreigners.

At 9,000 feet Bohm levelled out. The icing rapidly disappeared and, with clear aerials, the volume of the tiny station strengthened in his headphones. The needles of his radio compasses commenced to waver as he closed on the beacon until suddenly they swung through I80 degrees. This indicated that he had just crossed the station. Kiernan clicked the stopwatch - Bohm reduced power to set a rate of descent of 500 feet a minute. Kiernan called the time checks--Forty . . . fifty . . .Go! Bohm violently threw the Cat around on a reciprocal course, for this was no place for textbook gentle procedures. Back to the friendly beacon, one minute on the southerly heading, then around again to the north.

The greyness that entombed them began to lighten in texture. The queasy tightening of stomach muscles that ride with pilots descending through cloud in dangerous terrain relaxed.

North over the beacon . . . stopwatch clicks . . . no room for mistakes . . . round in another tight turn to the south . . . again to the north . . . and this time - yes, it’s breaking. The sheets of stratus are less dense. VR-HDS broke through between layers, and there, confronting their bulging eyes, was a sheer mountain wall where a level plateau should have been. Both pilots reacted immediately. Bohm flung the Catalina into a violent turn to port. Kiernan slammed both throttles and pitch controls as far forward as they would go. The Catalina clawed in a desperate bid for altitude in a tight, too tight climbing corkscrew. Instruments toppled, and Bohm’s only reference was the seat of his pants - which by now were unashamedly wet. Bohm reduced the rate-of-turn. Kiernan, caged and uncaged the artificial horizon several times, finally it settled into its designed function. Bohm continued the turn until the Catalina would climb no more.

Some forty minutes later the wandering needle of the radio compass seized on a signal and wavered round a point some ten degrees to port. Swiftly Bohm tuned in the stand-by compass and that too spun leisurely to the same heading. The radio operator confirmed the Morse lettering from his notebook and the tension on the flight deck lessened. Bohm considered the situation. His Catalina was staggering at 12,000 feet, the bearing of the station now showed he was on the safe side of the plateau. He gently wound the nose down and then disengaging the autopilot he set himself the task of orientating his arrival over the beacon. Repeated calls by his radio operator produced no response. Their only connection with an outer world was the KC, KC, KC of the homing beacon. That, at least, proved that some devoted soul in the wilderness below was doing his best to assist the airborne foreigners.

At 9,000 feet Bohm levelled out. The icing rapidly disappeared and, with clear aerials, the volume of the tiny station strengthened in his headphones. The needles of his radio compasses commenced to waver as he closed on the beacon until suddenly they swung through I80 degrees. This indicated that he had just crossed the station. Kiernan clicked the stopwatch - Bohm reduced power to set a rate of descent of 500 feet a minute. Kiernan called the time checks--Forty . . . fifty . . .Go! Bohm violently threw the Cat around on a reciprocal course, for this was no place for textbook gentle procedures. Back to the friendly beacon, one minute on the southerly heading, then around again to the north.

The greyness that entombed them began to lighten in texture. The queasy tightening of stomach muscles that ride with pilots descending through cloud in dangerous terrain relaxed.

North over the beacon . . . stopwatch clicks . . . no room for mistakes . . . round in another tight turn to the south . . . again to the north . . . and this time - yes, it’s breaking. The sheets of stratus are less dense. VR-HDS broke through between layers, and there, confronting their bulging eyes, was a sheer mountain wall where a level plateau should have been. Both pilots reacted immediately. Bohm flung the Catalina into a violent turn to port. Kiernan slammed both throttles and pitch controls as far forward as they would go. The Catalina clawed in a desperate bid for altitude in a tight, too tight climbing corkscrew. Instruments toppled, and Bohm’s only reference was the seat of his pants - which by now were unashamedly wet. Bohm reduced the rate-of-turn. Kiernan, caged and uncaged the artificial horizon several times, finally it settled into its designed function. Bohm continued the turn until the Catalina would climb no more.

At 13,000 feet with the aircraft in a gentle turn they held a council of war. Bohm, composure regained, was in favour of another attempt. Kiernan was equally prepared to do murder to prevent a repetition. The matter was taken from their hands when the direction aerial, weary of supporting its heavy load of glazed ice, broke away. They turned southeast towards the safety of Hong Kong.

The same cold front that had obstructed their primary purpose now brought them the blessing of a strong tail wind. They were conserving fuel. As the darkness embraced them any chance of identifying a landmark disappeared. With no serviceable direction finding equipment they faced the inevitable - they were lost.

The final miracle then occurred. A strong English voice advised them that RAF Radar Control had them on their screen. The best-kept secret in Southeast Asia was now public knowledge.

The radar controller brought them to the threshold of Kai Tak runway lit by emergency flares. With relief, Bohm brought his aircraft in for a smooth landing, 17 hours and 50 minutes after opening the throttles for Cheng-tu.

MATCO’s Operations Department returned to normality within a few days. Other flights of evacuation were carried out as the Mainland debacle ground to its inevitable conclusion. The Catalinas of MATCO brought succour to the peoples of Hainan Island, Mangtze, and many other beleaguered areas. Those that stayed saw the defenders of Chinese Nationalism tear Sun badges from caps and replace them with the Red Star of Communism. With a tired sigh the land settled behind a curtain of bamboo.

Before Captain Cos Cosgrove relates his second story The Distress of the Lady Ying he has an Epilogue to The Two Airfields of Cheng-tu.

Pacific Overseas Airlines (Siam) Limited, accepted the charter for a second try at Cheng-tu, and, solved the mystery of Captain Bohm’s failure. Its Skymaster enjoyed glorious weather in contrast to that of the lumbering Catalina. In unlimited visibility its crew realised the beacon’s signal came not from the Kuang-han airfield, but from Chiung-lai a strip 30 miles southwest of Cheng-tu. Tucked into a forbidding valley Chiung-lai’s western boundary was a 9,000-foot mountain range.

The approaching Communists had caused an early withdrawal from the plateau airstrip. Some patriots, determined to assist the pilots coming to their rescue, decided to relocate the beacon. In a buffalo-cart they transported it to the abandoned wartime strip. They gave no thought to the new location’s let down procedure.

Had Ross Bohm erred by a few seconds while descending on those tight one minute north and south legs another aircraft would have disappeared without trace.

The same cold front that had obstructed their primary purpose now brought them the blessing of a strong tail wind. They were conserving fuel. As the darkness embraced them any chance of identifying a landmark disappeared. With no serviceable direction finding equipment they faced the inevitable - they were lost.

The final miracle then occurred. A strong English voice advised them that RAF Radar Control had them on their screen. The best-kept secret in Southeast Asia was now public knowledge.

The radar controller brought them to the threshold of Kai Tak runway lit by emergency flares. With relief, Bohm brought his aircraft in for a smooth landing, 17 hours and 50 minutes after opening the throttles for Cheng-tu.

MATCO’s Operations Department returned to normality within a few days. Other flights of evacuation were carried out as the Mainland debacle ground to its inevitable conclusion. The Catalinas of MATCO brought succour to the peoples of Hainan Island, Mangtze, and many other beleaguered areas. Those that stayed saw the defenders of Chinese Nationalism tear Sun badges from caps and replace them with the Red Star of Communism. With a tired sigh the land settled behind a curtain of bamboo.

Before Captain Cos Cosgrove relates his second story The Distress of the Lady Ying he has an Epilogue to The Two Airfields of Cheng-tu.

Pacific Overseas Airlines (Siam) Limited, accepted the charter for a second try at Cheng-tu, and, solved the mystery of Captain Bohm’s failure. Its Skymaster enjoyed glorious weather in contrast to that of the lumbering Catalina. In unlimited visibility its crew realised the beacon’s signal came not from the Kuang-han airfield, but from Chiung-lai a strip 30 miles southwest of Cheng-tu. Tucked into a forbidding valley Chiung-lai’s western boundary was a 9,000-foot mountain range.

The approaching Communists had caused an early withdrawal from the plateau airstrip. Some patriots, determined to assist the pilots coming to their rescue, decided to relocate the beacon. In a buffalo-cart they transported it to the abandoned wartime strip. They gave no thought to the new location’s let down procedure.

Had Ross Bohm erred by a few seconds while descending on those tight one minute north and south legs another aircraft would have disappeared without trace.

In December 1949 Cathay Pacific’s sphere of operations extended to Hoi How, capital city of Hainan Island. For the briefest of moments there seemed scope to expand from Hoi How to Bangkok and Singapore. The first charter to Hoi How had an incident free flight. However, the next DC-3 flight avoided disaster by a hair’s breadth, as on take-off a heavy machine gun fired at it. When the luggage was off-loaded at Kai Tak it was perforated with bullets. Hoi How is the setting for Cos’s second story:

The Distress of the Lady Ying

The Lieutenant Governor of Hainan was in trouble. His wife had already left for Taipei but his beautiful concubine had not. The Lady Ying was not acceptable to Kuomintang society so the haven of Taipei was closed to her.

General Chin, with time running out, agonised over an alternative. Hundreds of his soldiers had disappeared into the mountains of the interior. He knew when they returned they would be wearing the badge of the Red Star.

As a last resort he appealed to Macao where several of his military colleagues had taken refuge. In a process hard to fathom his appeal moved through Cathay Pacific and wound up on the desk of MATCO’s operations manager, Captain James Ennis.

By coincidence the company’s crews were, in that month of April 1950, fully committed to the gold run. This was the company’s bread-and-butter so Ennis was left with the ball in his court.

The company had lately bought a third Catalina mainly as a stand-by plane. It was of indeterminate age and questionable flying qualities, yet Ennis had VR-HDH prepared for the Hoi How adventure.

Then, Mainland China had overcome Nationalist troop resistance except for a tiny area inside the Burmese border called The Golden Triangle. There the ragged beaten troops of General Li Mi protected an area rich with opium, while the Hainan garrison was thinly spread with undisciplined and unpaid conscripts. Hainan Strait separated the island, and was trafficable by foot at low tide.

Ennis mounted his rescue of the damsel in distress. With no available co-pilot he merely dispensed with one. He found a mechanic with prior knowledge of the terms of the charter, cowering under a bench. Then he shanghaied a radio operator that a doctor had excused from duty on medical grounds.

In an atmosphere other than congenial they departed on the two and a halfhour flight. Only after landing did Ennis realise that the airfield was unserviceable with potholes of unfathomable depth strewing the runway. The ragged soldiers in sight seemed disinterested at the Cat’s arrival.

His beautiful passenger and her entourage were nowhere in sight. A lesser man would have about-faced without stopping engines, but when sober Ennis was not easily discouraged – and that day, without a copilot, he was sobriety personified.

His commanding appearance, and his mechanic interpreting, learned that the lady had waited there for several days. She had returned to a hotel in the city. After much haggling and flashing U.S. currency, a jeep appeared and whisked the Captain off to a hotel that glowed in its decrepitude, in a city that emulated the hotel’s description. He soon found the truly beautiful Lady Ying and her two small children.

Ennis made it clear that he was anxious to be off, but the lady would have none of this. She invited him to dinner that evening, and deferred departure ‘till the morrow’. The gallant captain could only concur, however he took the precaution of removing the distributor cap from the jeep. Then he retired for a quick pre-dinner kip.

One Chinese dinner is much like another, Ennis mused. The quality of the grog was his standard for grading a dinner. This one immediately impressed him for at this last ditch Kuomintang dinner the best Scotch flowed like water.

The evening passed in a misty haze and endless rounds of toasts. Many who attended would board his aircraft the next morning with a total regard for available seating. In a gesture of magnanimity Ennis invited all the other diners to be there as well. At the evening’s end he contemplated a discreet knock on the Lady’s door, but the muscular appearance of her entourage discouraged him.

He seemed to have slept for only a few minutes when he was shaken violently. A voice screamed for him to get up. He muttered incoherently and turned over. A bucket of water brought him to his feet. With a bellow of rage he grasped his tormenter - his near hysterical mechanic screeched `the Reds have landed. They walked across the Straits at low water last night—you can hear the shooting.’

He took the stairs two at a time, throwing the distributor cap to the mechanic. Outside the hotel the driver of an ancient bus ran off into the darkness leaving his passengers huddled beneath the window level. Ennis dived behind its wheel and sent it rocketing down the road to the airport. He crashed through the wire that marked the strip’s perimeter, and headed straight for his now beautiful Catalina.

The passengers needed no urging as they scrambled aboard. Ennis followed his mechanic through the hatch and as he slammed it shut he knew the mechanic was turning the propellers. All he had to do was flick on the ignition switches and his engines would roar. Ennis peered over the nose to see all was clear, then slowly, with a sigh, he switched the ignitions off again.

Before the props had begun to wind down, the mechanic was out of his tower, eyebrows raised in mute inquiry. Not wasting words, Ennis jerked a thumb forward indicating a group of uniformed men. They flanked two others who crouched behind a heavy Vickers machine-gun that they aimed at the Catalina’s cockpit window.

Ennis’ stomach muscles contracted as he saw that Red Stars had replaced Sun badges on the men’s caps. Ennis ordered his mechanic to open the hatch and parley with the soldiers. At that moment the Lady Ying touched his elbow. Ennis pointed through the window at menacing machine-gun.

No words were necessary. From the depths of the valise, a servant guarded, she withdrew a small oblong package. She loosened the wrapping and handed it to Ennis with a fleeting smile. He drew a sharp breath for his hand held a dozen taels of gold. Ennis slammed open his sliding window and beckoned the leader of the group. As the officer reached viewing distance Ennis lifted the corner of the wrapping and pointed meaningly at the machinegun. The message got through. A barked command removed the gun the parcel was tossed out and swiftly pocketed. Within a few minutes the Catalina was on her way to Macao. The rough diamond pilot had rescued a beautiful damsel in distress.’

General Chin, with time running out, agonised over an alternative. Hundreds of his soldiers had disappeared into the mountains of the interior. He knew when they returned they would be wearing the badge of the Red Star.

As a last resort he appealed to Macao where several of his military colleagues had taken refuge. In a process hard to fathom his appeal moved through Cathay Pacific and wound up on the desk of MATCO’s operations manager, Captain James Ennis.

By coincidence the company’s crews were, in that month of April 1950, fully committed to the gold run. This was the company’s bread-and-butter so Ennis was left with the ball in his court.

The company had lately bought a third Catalina mainly as a stand-by plane. It was of indeterminate age and questionable flying qualities, yet Ennis had VR-HDH prepared for the Hoi How adventure.

Then, Mainland China had overcome Nationalist troop resistance except for a tiny area inside the Burmese border called The Golden Triangle. There the ragged beaten troops of General Li Mi protected an area rich with opium, while the Hainan garrison was thinly spread with undisciplined and unpaid conscripts. Hainan Strait separated the island, and was trafficable by foot at low tide.

Ennis mounted his rescue of the damsel in distress. With no available co-pilot he merely dispensed with one. He found a mechanic with prior knowledge of the terms of the charter, cowering under a bench. Then he shanghaied a radio operator that a doctor had excused from duty on medical grounds.

In an atmosphere other than congenial they departed on the two and a halfhour flight. Only after landing did Ennis realise that the airfield was unserviceable with potholes of unfathomable depth strewing the runway. The ragged soldiers in sight seemed disinterested at the Cat’s arrival.

His beautiful passenger and her entourage were nowhere in sight. A lesser man would have about-faced without stopping engines, but when sober Ennis was not easily discouraged – and that day, without a copilot, he was sobriety personified.

His commanding appearance, and his mechanic interpreting, learned that the lady had waited there for several days. She had returned to a hotel in the city. After much haggling and flashing U.S. currency, a jeep appeared and whisked the Captain off to a hotel that glowed in its decrepitude, in a city that emulated the hotel’s description. He soon found the truly beautiful Lady Ying and her two small children.

Ennis made it clear that he was anxious to be off, but the lady would have none of this. She invited him to dinner that evening, and deferred departure ‘till the morrow’. The gallant captain could only concur, however he took the precaution of removing the distributor cap from the jeep. Then he retired for a quick pre-dinner kip.

One Chinese dinner is much like another, Ennis mused. The quality of the grog was his standard for grading a dinner. This one immediately impressed him for at this last ditch Kuomintang dinner the best Scotch flowed like water.

The evening passed in a misty haze and endless rounds of toasts. Many who attended would board his aircraft the next morning with a total regard for available seating. In a gesture of magnanimity Ennis invited all the other diners to be there as well. At the evening’s end he contemplated a discreet knock on the Lady’s door, but the muscular appearance of her entourage discouraged him.

He seemed to have slept for only a few minutes when he was shaken violently. A voice screamed for him to get up. He muttered incoherently and turned over. A bucket of water brought him to his feet. With a bellow of rage he grasped his tormenter - his near hysterical mechanic screeched `the Reds have landed. They walked across the Straits at low water last night—you can hear the shooting.’

He took the stairs two at a time, throwing the distributor cap to the mechanic. Outside the hotel the driver of an ancient bus ran off into the darkness leaving his passengers huddled beneath the window level. Ennis dived behind its wheel and sent it rocketing down the road to the airport. He crashed through the wire that marked the strip’s perimeter, and headed straight for his now beautiful Catalina.

The passengers needed no urging as they scrambled aboard. Ennis followed his mechanic through the hatch and as he slammed it shut he knew the mechanic was turning the propellers. All he had to do was flick on the ignition switches and his engines would roar. Ennis peered over the nose to see all was clear, then slowly, with a sigh, he switched the ignitions off again.

Before the props had begun to wind down, the mechanic was out of his tower, eyebrows raised in mute inquiry. Not wasting words, Ennis jerked a thumb forward indicating a group of uniformed men. They flanked two others who crouched behind a heavy Vickers machine-gun that they aimed at the Catalina’s cockpit window.

Ennis’ stomach muscles contracted as he saw that Red Stars had replaced Sun badges on the men’s caps. Ennis ordered his mechanic to open the hatch and parley with the soldiers. At that moment the Lady Ying touched his elbow. Ennis pointed through the window at menacing machine-gun.

No words were necessary. From the depths of the valise, a servant guarded, she withdrew a small oblong package. She loosened the wrapping and handed it to Ennis with a fleeting smile. He drew a sharp breath for his hand held a dozen taels of gold. Ennis slammed open his sliding window and beckoned the leader of the group. As the officer reached viewing distance Ennis lifted the corner of the wrapping and pointed meaningly at the machinegun. The message got through. A barked command removed the gun the parcel was tossed out and swiftly pocketed. Within a few minutes the Catalina was on her way to Macao. The rough diamond pilot had rescued a beautiful damsel in distress.’