Tiddly Winks

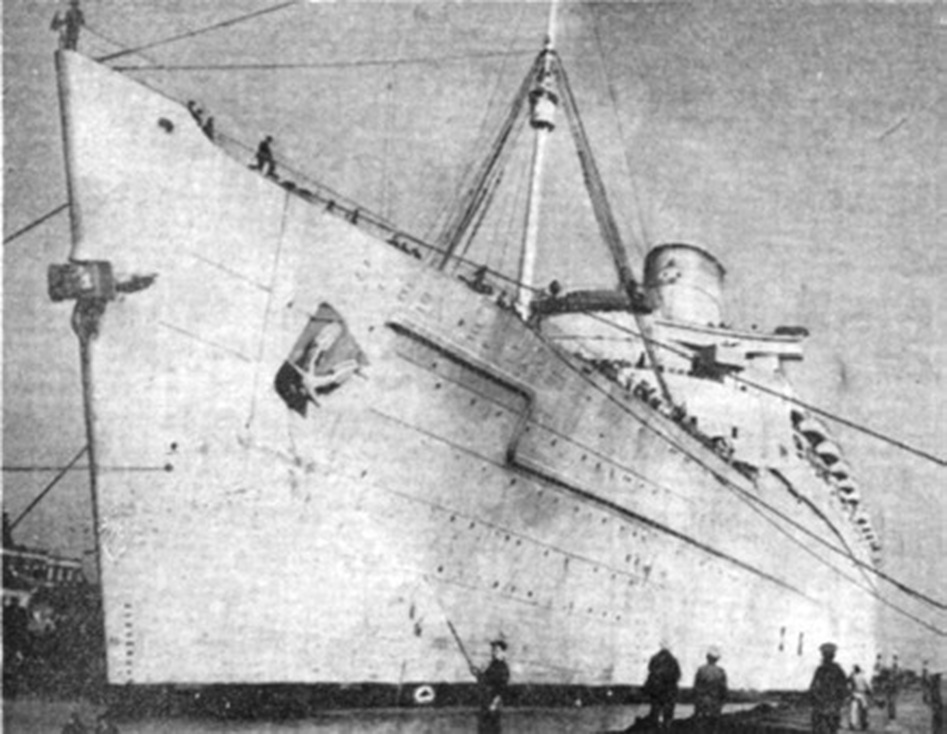

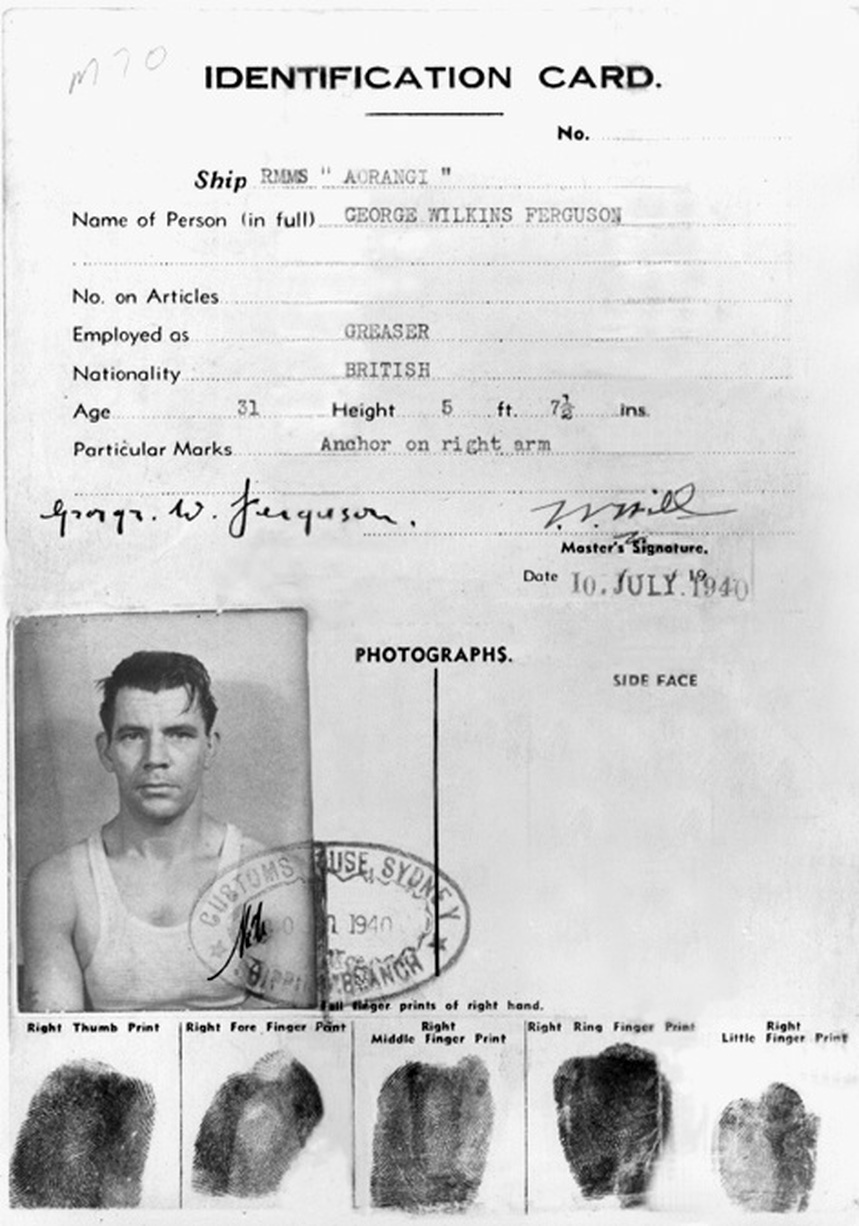

The Mungana episode hardened my entrails and never again did I suffer mal de mere in boat or plane. My next posting went a long way to restore my faith in floating objects. On 4 March 1941 I arrived at the Sydney Harbour Master’s building and was chosen from a big group of seamen to sign articles for service on the H.T. (Hired Transport) Queen Elizabeth. Ahead of me was a sullen looking seaman who walked with a limp and the bearing of a man deprived of his morning punch-up. As we waited our turn to register we began to chat. His appearance belied his demeanour and I found myself in the company of a charming man. From that moment George Ferguson and I became inseparable. He guided me through the mazes and pit-falls of life, as would a father. Then, the Queen was the largest ship in the world. Built for the Southampton to New York run, she had not made her debut as a passenger liner. Her massive turbines developed 158,000 horsepower that hurled her 83,673.09 tonnage at unheard of speeds. According to my mentor that turn of speed nudged 40 rather than 35 knots and earned my heartfelt thanks when we cleared the Suez port of Taufiq (Tewfik) with undignified haste. The bridge had received a signal that a massive air raid was advancing on Alexandria. Coincidentally, we had just discharged my old mates of the 1st Australian Anti-Aircraft Regiment.

I have affectionate memories of that floating Leviathan. Many of them embrace the nightmare of watch work and food standards, while others broadened my horizons, especially where sexual preference reared its head. The Queen, and George, helped me emerge as a novice grade man-of-the world, free from the manacles of naivety and bigotry.

During our return to Australia the Queen dry-docked in Singapore where George and I walked the length of her keel. It was an awesome feeling to find that massive weight resting just inches above our heads. Then in the evening we searched for inner soles to protect George’s aching feet, finding them in a shop that sold only deceased’s shoes. We then stumbled into what appeared a toilet only to find it was the main VD clinic. It was spotlessly clean with a dearth of clients. The Chinese doctor, the image of Fu Man Chu, was devastated to learn we had come in just for a leak. He brightened up when he suggested how charmed he would be if we allowed him to give us a check up – on the house of course. His crestfallen face at our rejection was the signal for his two assistants with the drooling chops of unemployable eunuchs to sidle between the door and us. Just when I resigned myself to speaking in a high pitched voice, George whispered in the doctor’s ear. The doctor beamed and the eunuchs returned to their opium divan. After a respectable silence I asked George what he whispered. He had told the doctor that he was Sydney’s acknowledged authority on abortion, and later I learned that this was the mildest exaggeration of the truth.

I recall the raid by ship’s security to recover fans filched from staterooms to combat the heat of the Arabian Sea. I heard the commotion from a distance and had the presence of mind to toss my fan through the porthole, avoiding the hefty fines imposed on the less fleet of creative action. When we crossed the Great Australian Bight we witnessed mountainous seas that made the aft gun deck untenable. Though it was more than fifty feet above the Plimsoll line the seas broke right over it.

Returning from watch one evening I passed a quiet companionway. I saw our Peggy (a sailor who looks after our Mess) flagrante delicto with a colleague who was enjoying every thrust and singing – Tiddly winks, old boy. Tiddly winks, old bean. Did you ever see a sailor up a dead sardine? Said the captain of a whaler as he whopped it up a sailor . . . ending his ditty with a deep contented mewing sound.

I roared my disgust and got the advice, in unison, to bugger off. Later my colleague calmly told me he was performing a remedial treatment. You see, said he, the poor fellow suffered from piles and he merely helped push them back! I found myself applauding both their savoir fare and the spur of the moment adjective that so suited their activity!

I signed off the QE on 25 June 1941, and the very next day found me belted into the cockpit of DH 60 Gipsy Moth VH-UFV with craggy-faced Howard K. Morris patiently demonstrating how to fly her straight and level.

During our return to Australia the Queen dry-docked in Singapore where George and I walked the length of her keel. It was an awesome feeling to find that massive weight resting just inches above our heads. Then in the evening we searched for inner soles to protect George’s aching feet, finding them in a shop that sold only deceased’s shoes. We then stumbled into what appeared a toilet only to find it was the main VD clinic. It was spotlessly clean with a dearth of clients. The Chinese doctor, the image of Fu Man Chu, was devastated to learn we had come in just for a leak. He brightened up when he suggested how charmed he would be if we allowed him to give us a check up – on the house of course. His crestfallen face at our rejection was the signal for his two assistants with the drooling chops of unemployable eunuchs to sidle between the door and us. Just when I resigned myself to speaking in a high pitched voice, George whispered in the doctor’s ear. The doctor beamed and the eunuchs returned to their opium divan. After a respectable silence I asked George what he whispered. He had told the doctor that he was Sydney’s acknowledged authority on abortion, and later I learned that this was the mildest exaggeration of the truth.

I recall the raid by ship’s security to recover fans filched from staterooms to combat the heat of the Arabian Sea. I heard the commotion from a distance and had the presence of mind to toss my fan through the porthole, avoiding the hefty fines imposed on the less fleet of creative action. When we crossed the Great Australian Bight we witnessed mountainous seas that made the aft gun deck untenable. Though it was more than fifty feet above the Plimsoll line the seas broke right over it.

Returning from watch one evening I passed a quiet companionway. I saw our Peggy (a sailor who looks after our Mess) flagrante delicto with a colleague who was enjoying every thrust and singing – Tiddly winks, old boy. Tiddly winks, old bean. Did you ever see a sailor up a dead sardine? Said the captain of a whaler as he whopped it up a sailor . . . ending his ditty with a deep contented mewing sound.

I roared my disgust and got the advice, in unison, to bugger off. Later my colleague calmly told me he was performing a remedial treatment. You see, said he, the poor fellow suffered from piles and he merely helped push them back! I found myself applauding both their savoir fare and the spur of the moment adjective that so suited their activity!

I signed off the QE on 25 June 1941, and the very next day found me belted into the cockpit of DH 60 Gipsy Moth VH-UFV with craggy-faced Howard K. Morris patiently demonstrating how to fly her straight and level.